Some Notes on

the early Discoverer flights

Sven Grahn

In early 1958, a

few months after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik-1, President Eisenhower

authorized the development of a top-priority reconnaissance satellite

project operated by the CIA Directorate of Science & Technology

with assistance from the US Air Force. It was used for photographic

surveillance of the Soviet Union, China and other areas from 1960 until May

1972. The project's code name is CORONA, but to hide its true purpose, it

was given the cover name Discoverer and described as a scientific research and

technology development program.

There were 144 Corona satellites launched, 102 of which

returned useful pictures. Detailed accounts of this program can be

found here, here, and here.

The Discoverer program was very

much in the media in my youth. This may seem strange for a highly classified

program, but the cover story was successfully used and lots of technical details

were released at the time. Here I will just touch upon a few items about this

program that has caught my interest.

The flight of

Discoverer-1

|

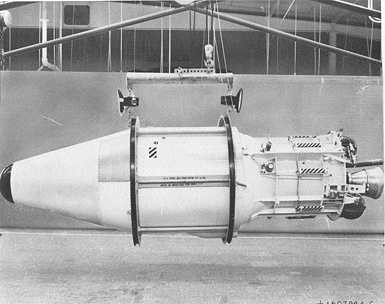

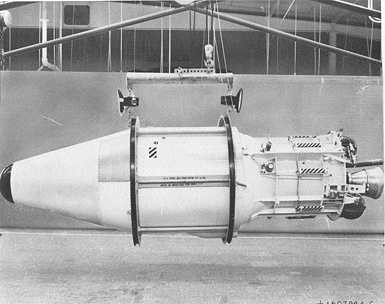

A USAF photo of

Discoverer-1.

|

The first Discoverer launch attempt that took place at

Vandenberg Air Force base in California on 21 January 1959 failed because of the

launch vehicle. The second launch took place on 28 February 1959. Initially the

satellite was reported to be in orbit, but I have always wondered what really

happened. It seems that contact was lost with the spacecraft very early in the

mission. In Swedish media the satellite was called "the whispering satellite".

Even the Swedish radio telescope at

Råö on the Onsala peninsula outside Gothenburg was reported to have picked

up weak signals.

I asked Dwayne Day, the foremost expert on the

U.S. reconnaissance satellite effort, about this mystery and here is his

reply:

"The person I talked to

was Frank Buzard ("buz ard") who was the test officer for Discoverer. He

was assigned to write up the reports on the launches after they were

over. Of course, Discoverer failed repeatedly for the first dozen

missions or so (although a few reached orbit). Buzard has a very good

memory and remembers what specifically went wrong with most of the early

missions. In the case of Discoverer 1, I think that the Air Force launched it

and they had no bad telemetry during the launch, but the telemetry did not

follow the entire Agena burn. Based upon something like 50% of the Agena

data being good, the Air Force assumed that the other 50% must be good and it

reached orbit. So they issued a press release saying it had reached orbit.

'Well that's a bad

assumption,' Buzard told me, and said that he did not like to assume anything

as far as rockets were concerned. So the Air Force said it was in orbit

and then everybody listened to hear it fly overhead. At the time, the

idea of getting a radar skin paint on a satellite was still pretty much

nonexistent. They relied upon picking up the radio beacon. But

nobody got a good beep beep beep. They had one or two stations that claimed

that they got a couple of beeps, but nothing more substantial.

I think that Buzard

looked at some data printouts and tried hard to interpret some spikes out of

the background noise as a signal from the satellite. He then turned this

into a report saying what the Air Force wanted him to say, but he was never

happy with it. And nobody else ever got good beeps from the satellite. Later,

after Discoverer was clearly successful (more than any of the public realized

at the time), those involved were willing to concede that they had probably

bent the data to serve public relations purposes .."

The flight of

Discoverer-2

Discoverer-2 was launched from Vandenberg Air Force

base at at 2122 UT on 28 February 1959. It entered an orbit between 239

and 346 km at an inclination of 89.9 degrees, a truly polar orbit -

very rare in the history of space flight (2). It was widely reported

as having come down on Svalbard and this event has even stimulated the Alistair

MacLean's novel "Ice Station Zebra" (1963) and the movie with the same name

(1968). The capsule was never found and the fate of the mission remains somewhat

of a mystery.

An internal CIA publication describes this flight as

follows(3):

"... The [U.S.] Air Force reported on 15 April that

plans to recover the capsule near Hawaii had been abandoned and that the

capsule might descend somewhere in the Arctic. The announcement slightly

understated the known facts. The capsule had ejected in the 17th orbit as

planned, but a programming malfunction (actually a human programming

error) had caused the ejection sequence to be initiated too early. The

capsule was down, probably somewhere in the near vicinity of the Spitsbergen

islands north of Norway. In fact, there were later reports that the falling

capsule had actually been seen by Spitsbergen residents. The Air Force

announced on the 16th that the Norwegian government had authorized a search

for the capsule which would begin the following day. Planes scoured the area,

and helicopters joined the search on the 20th. Nothing was found, however, and

the search was abandoned on the 23rd. [two lines deleted by censors] ..."

There

were many reports and rumors that the capsule had been recovered by Soviet

authorities using staff based at Soviet mining sites at Spitsbergen. However as(4) recounts

"... Not everyone was convinced that the capsule had

been recovered. Major Buzard initially felt that the capsule had come down on

Spitsbergen, but later changed his mind and suggested that the vehicle

probably came down in the water and sank, or never came down at all, suffering

the same fate as later satellites that had problems with their retro-rocket

de-spin system. There was no evidence on the ground that Discoverer-2

had been recovered. 'Witnesses' had been told exactly what to look for and may

have merely repeated what they were told ..."

Dwayne

Day has written an excellent

account

of

the flight of Discoverer-2 and the attempts to recover it.

As one can see from the plot below,

which shows the groundtrack for the climb out of Vandenberg on 13 April and

the planned recovery orbit on 14 April (landing would have occurred on the 15th,

Universal Time), the ground track of Discoverer-2 indeed passed over Spitsbergen,

and also straight over my home town - Stockholm, Sweden!

Discoverer-13, the first recovery from

orbit

Flight profile

Discoverer-13 was launched in a fog

bank from Vandenberg AFB at 2038 UT on 10 August 1960 and entered an orbit

between 253.5 and 690 km at 82.85 degrees inclination. At 2115 UT (5) on 11 August the

recovery sequence was initiated when the spacecraft was over the "Indian Ocean

Station" in the Seychelles. The station at Kodiak island transmitted the capsule

ejection command at 2311 UT on orders from the USAF Satellite Test

Control Center at Sunnyvale, California - "The Blue Cube". The parachute

opened at 2326 UT and the capsule descended about 480 km northwest of Hawaii.

The capsule was recovered at 0130 UT on 12 August 1960 200 km north-west

of Honolulu. A helicopter from Haiti Victory picked up the capsule.

The map below shows the ground trac for the launch out

of Vandenberg AFB on 10 August 1960 and the two last passes over the

Pacific the following day. The plots have been made with orbital element sets

from the old NASA OIG web site.

Dan Hill's eyewitness account

of the recovery of Discoverer-13

USAF Generals T.D. White (left) and Bernard

Schriever,

Col. Charles G. "Moose" Mathison,

and Discoverer-13 capsule. Note

beacon antenna

- see below. USAF

photo. |

In late

2009 I received a very interesting message from Dan Hill (9)

who participated in this historic event:

"... I was part of

the 6593rd Test Squadron "Special", which we had formed in the fall of 1958 at

Edwards AFB, CA., I occasionally search for any new data or input.

The purpose of our new squadron was to develop, test and practice aerial

recoveries of future space capsules. Our new Squadron relocated to

Hickam AFB, Hawaii, in early December 1958, and we continued practice

missions.

Our aircrew was very

close to Discoverer 13 space capsule when it re-entered Earth right on target

on August 11, 1960. We were prime recovery position, but unfortunately

we were directed away from the capsule by one of the control aircraft and by

the time our navigator realized they had sent us in the opposite direction, it

was too late.

He altered our course,

we flew back to where we should have been all along, and found the capsule and

parachute floating in the ocean. By that time another one of our

recovery aircrews were flying over the area as well. We dropped dye

markers and smoke bombs and flew surveillance for several hours till the U.S.

Navy got there and retrieved the historical capsule and chute into a

helicopter and flew them back to their ship

..."

Discoverer-14, the first aerial recovery

A mere

eight days after the launch of Discoverer-13 the next satellite is launched.

Thus, Discoverer-14 was launched from Vandenberg AFB at 1957 UT on 18 August

1960. The film capsule from Discoverer-14 was snagged by a n airplane over the

Pacific at 2314 UT on 19 August 1960. In 1999 Bill Obenauf wrote to me

(6)

about Disoverer-14:

"I

worked on Corona at Vandenberg 1959 - 1967. Your pictures are very familar. In

my desk drawer, under this keyboard, is a bolt from Discoverer 14, the first

capsule that brought back film. Thanks for bringing back many

memories."

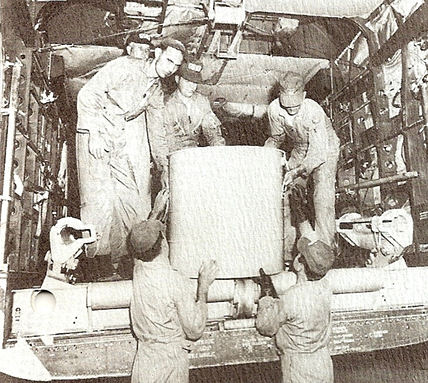

|

Snagging a capsule with a C-119 plane. This

picture

shows a practice run. USAF

photo

|

Dan Hill wrote to me

in 2009 (9) and described the recovery of

Discoverer-14 and his part in

it:

"... The following week, our aircrew was way, way down

range in the outfield of the recovery area, the least desirable recovery

position for Discoverer-14. As we all waited and waited, our navigator

finally received a signal, which became stronger. He directed our

aircrew to the signal, we scanned the skies overhead and finally our aircraft

commander saw the orange/silver parachute and capsule high above us. As

you know, history was in the making again, when on our third and last possible

aerial recovery attempt, we snagged the parachute with capsule attached [at

2600 meters altitude (11)

], had it in tow

and our winch operator brought them to the rear of our aircraft. At that

point, we Loadmasters lifted and pulled the first historical aerial recovered

chute and space capsule on board our now famous aircraft.

I just turned 21

years old (the youngest of our aircrew), the day that Discoverer-14 lifted off

and when we returned to Hickam AFB the next afternoon on August 19, 1960 with

the capsule, I was advised by our wing commander in front of the spectators

and press people as I was presented a birthday cake: 'Danny, yesterday they

sent your birthday present into orbit and today it was delivered to

you'. We were naturally, very proud of our historical catch, but

the fact that now, Discoverer-14 space capsule had been officially designated

my birthday present and my picture with me and cake went out to various parts

of the world. That made me that much prouder ..."

Newspaper clipping showing Dan

Hill receiving his

birthday

cake. |

The primary recovery area

encompassed a 320 x 96 km rectangle, and six C-119's and a C-130 flew within

this "ballpark" area. Three other C-119's, including the actual recovery

aircraft, patrolled an "outfield" area embracing an additional 640 km. the

capsule was hauled aboard the aircraft 30 minutes from the time the navigator

had first reported a steady signal from the capsule's radio beacon (11).

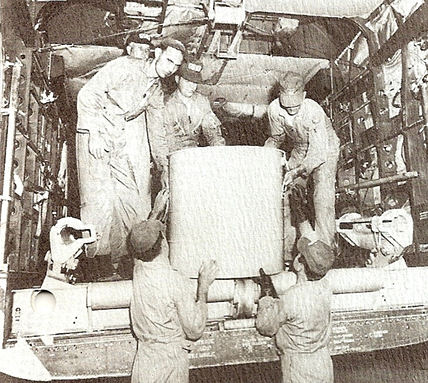

Air crew of C-119 (tail nr 18037) unload the

canister with the Discoverer-14

capsule inside. Dan Hill is the

righthand person standing on the ground. |

Discoverer-14 recovery crew and its

commander Captain Harold E Mitchell

being praised by Pacific

Air Force Commander General Emmett O'Donnell.

The stand in front of their

C-119 with tail number 18037. This plane is pre-

served.

Dan Hill is at the far right of

the line of airman. USAF

photo. |

Discoverer telemetry, command, and tracking systems

Telemetry and command system

|

Telemetry antennas on an Agena-A. USAF photo.

|

The

Agena stage/spacecraft used an FM/FM telemetry system initially operating

on P-band (215-260 MHz) in the VHF range, called "Type V" (1). Orbital

determination and command reception was provided by an S-band beacon

transponder.

The telemetry system relayed 85 data

points(1)

.

Bill Obenauf, who worked

for Lockheed at Vandenberg Air Force Base, gave more details about the early telemetry system

of Corona (10):

"The Agena telemetry was FM/FM during the first few years.

It used 17 channels of sub-carrier oscillators modulating an FM transmitter. A

few of the oscillators were commutated using 60 point motor driven 'switches'.

Some oscillators monitored film rollers in the camera. One of the commutator

points monitored film quantity in the capsule."

Bill

Obenauf also described the command link (10)

:

"Commands were sent up from tracking stations to the

Agena via the S-band link to the tracking beacon. Two pulses, ten microseconds

spacing, were decoded by the agena beacon to generate a reply to the ground

tracking radar station. A third pulse, between the other two, was modulated

position-wise at audio rates to generate commands to the Agena. S-band was 10

cm [SG: 3 GHz]."

In (1) the Philco radar transponder

is said to have responded to a combination of two audio tones of the middle

pulse. Fifteen commands

from the decoder were possible by using

six audio frequencies in all possible combinations of two.

There was a

mechanical sequencer for executing commands out of sight of grund stations. It

had two magazines of punched Mylar tape. The programmer could execute twenty-six

commands repeatedly for 256 orbits. There was also a programmer for 52

preprogrammed commands and a flight loadable storage register for 32 commands(1)

. In addition to the main command

system there was also a UHF back-up command system.

Telemetry and recovery beacon

frequency

We can

learn something about the frequencies used for the VHF telemetry system by

referring to observations made by radio trackers at the time, and "leaks" in the

literature. The telemetry frequencies used were in P-band and the most common

telemetry frequency during early flights was 237.8 MHz. It is not easy to locate

antennas for this frequency band on pictures of Agena vehicles. Only in a

picture of what purportedly is Discoverer-1 can a ring of antennas be seen

around the engine compartment of the Agena rocket stage which formed part of the

spacecraft. These antennas seen in the picture (the stripes on the antennas

coloured red in the picture) below are probably so-called quadra-loop antennas

and the size is compatible with frequencies in P-band.

Bill Obenauf also wrote:

"... I asked a friend, who also worked on

Corona. After thinking about the Agena telemetry radio carrier frequency

238 MHz comes to mind Anyhow, the Corona capsule beacon used a carrier

of 235 Megacycles (we didn't use mega hertz in those days). It was

amplitude modulated by a tone that sounded like weep - weep - weep. The

period of the "weep" varied depending on events that happened during the

recovery, like parachute deploy

..."

We can also get

a glimpse of what the Agena telemetry sounded like by listening

to Agena signals on P-band picked up by satellite trackers at the University of Florida Student

Tracking Station in the 60's while they monitored telemetry from Agena target

vehicles for the Gemini program.

Radar transponder

|

Waveguide antenna seen on an Agena stage on display

at

the National Air and Space Museum in Washington

D.C. |

Gemini-Agena had two radar transponders, one with a

downlink in S-band at 2910 MHz and another in C-band with a downlink at 5765

MHz. A few years ago, there was an Agena on display at the National Air and

Space Museum in Washington D.C. It carried device that looked like the sketch on

the right. The size and general look of this device suggest that it is a

waveguide antenna for C-band, possibly the radar transponder frequency 5765 MHz.

Ground station

operations

On a listserver, I cannot recall which, I found the

following personal memory from someone working at USAF tracking stations in the

early 60's (7)

:

"... I worked at several of the Air Force tracking

stations for these things including Vandenberg AFB in the early 60's. The

satellite command officer, or civilian was told what commands to send after we

turned the bird on. Any indications they got from the consoles was minimal and

certainly didn't let you know about film. It would be a reading, like: meter

number 5 reads 50 percent.

For

each 'pass' we set up the decommutator outputs to drive specific meters. We

had no idea what these meters were reading, but in real time we gave out those

numbers. So the sequence would be:'KODI Transmit command 1020'. Satellite

turns on-telemetry, decommutators lock onto the downlink, signal-meters start

to act. During the short pass we give the satellite command console operator

the read-outs. The console operator passes them to the 'Blue Cube'. He

then checks what is required and then sends back a response; 'Indi, send

command 2050, command 1010 and command 1230.' ...

...

The console operator then dials up those commands, they are picked from a

library of commands back in the computer room running a SperryRand computer,

and then he presses transmit. He then tells Palo Alto the commands he sent.

The only site that sent deorbit commands was the KODI site at Kodiak,

Alaska. The satellite would be heading south toward Hawaii the pickup

area ..."

Antennas on the

re-entry vehicle

The eleventh International Astronautical Congress (IAC) was

held in Stockholm in August 1960 as I have described in another article at

this web site. As you can read there a very detailed mock-up (actually a

"mechanical analog") of the Discoverer re-entry vehicle (including retro-rocket)

and film capsule was on display at the Congress and I (at the age of fourteen)

was given the task of describing it to the general public during "open day" on

the Congress' last day (see picture below), actually some fourty hours after

that the capsule from Discoverer-14 was snagged by a a C-119

plane.

I hold my hand on

the Discoverer film capsule on display at the eleventh International

Astronautical

Congress. The venue is the Royal Institute of

Technology in Stockholm. The date is 21 August 1960. I

have

struggled to bring myself out of the horribly bad contrast of this picture. |

I also took some close-up pictures of the display. The

picture below shows the heat shield with the retro-rocket ona sheet metal cone

on the lower left and part of the film capsule on the upper

right.

Discoverer heat shield with

retro-rocket on top and film capsule (upper

right) on display at IAC

1960 in Stockholm. |

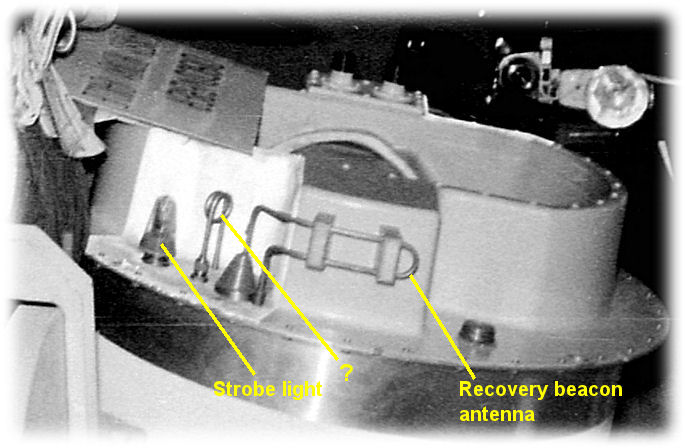

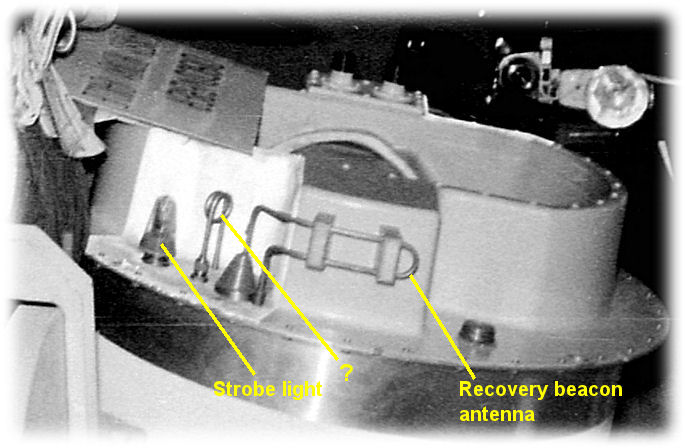

By blowing up the little part of this picture that shows

the film capsule and turning it 90 degrees we can examine some deails on top of

the capsule.

|

Details on top of the

Discoverer film capsule on display at the IAC 1960 in

Stockholm.

|

I can state with certainty

that device on the left is a strobe light and the device on the right looks like

a typical loop antenna half a wavelength long (see this article) with

one end grounded in the capsule chassis and the other end insulated from chassis

and fed by a transmitter. The size matches relatively well the beacon frequency

235 MHz. But what is the device marked "?"? It looks like an antenna too

with one end grounded and the other fed by a radio device. But what is the

frequency and purpose? Could it for a frequency in the range 1-2 GHz and is it a

radar transponder antenna? Interestingly this device can not be found on

pictures of the recovered Discoverer-13 capsule. On one side of this capsule one

can see the strobe light an a hole where "?" is seen above. On the other side of

the capsule there is no strobe light either, just a hole. The "?" can be seen in

a picture by James Plummer.

Re-entry

and recovery sequence

In

(11) Some basic numbers are

given:

-

The reto-rocket impulse is

directed backwards 60 degrees below the local horixontal.

-

Re-entry vehicle size and

mass:

-

Heat shield length 686

mm, diameter <= 838 mm

-

Retrorocket cone length

approx 330 mm

-

Total re-entry vehicle

length approx 1016 mm

-

Approximate mass 160

kg

-

Radio blackout ended at

40.5 km

-

Parachute deployed at 15-16.5 km altitude. This is

very high and probably intended to provide a long descent time so that the

aircraft on patrol would have a chance to reach the capsule

for snagging. According to (1) the rate of descent varied

between 15 m/s and 6 m/s and the total time of descent from 15 km was about 30

minutes.

-

Distance from retrofire to

recovery was about 3200 km.

-

The recoverable film

capsule weighed approx 38 kg

Orbital parameters of

early Discoverer missions

The obital elements of early Discoverer satellites were similar between flights,

but not identical. To able to find a pattern

I plotted the mean motion (revolutions/day) against the inclination

for the first 39 launches that made it to orbit. (See the figure

below) The inclination varied less than the mean motion. It seems that the

orbital period (together with the inclination) was used to achieve coverage

of differenet areas. To prove this and extenisve study of the coverage over the

Soviet Union of each of these missions. I am not sure the photo coverage of all

these missions have been made public.

References

-

Robert A. McDonald (ed.),

"Corona, Between the Sun & the Earth, The first NRO reconnaissance Eye

in the Sky", American Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing,

Bethesda, MD, 1997.

-

D.G. King-Hele et al, "The RAE Table of Earth Satellites",

1957-1989", Royal Aerospace Establishment, 1990.

-

Kenneth E. Greer, "Corona", Studies in Intelligence,

Supplement, 17 (Spring 1973): 1-37. Reprinted in "Corona: America's first

Satellite program", Kevin C. Ruffner (ed) , CIA, 1995.

-

Dwayne Day et al, "Eye in the Sky", Smithsonian

Institution Press, 1998 p.53.

-

Booda, "First Capsule";

Witkin, "Washington to Hail"; Office of the Director of Defense Research

and Engineering, Military Space Projects No. 11, p.3. (Reference

given in Jeffrey T. Richelson, "America's Secret Eyes In Space",Harper &

Row, 1990)

- E-mail from Bill Obenauf on 6 March 1999.

-

If someone recalls that he sent this message, please let

me know!

- Relayed to me by Volker Baumann

- E-mail from Dan Hill, 30

December 2009.

- E-mail from Bill

Obenauf, 12 March 1999.

- "Summary.

US Air Force Discoverer satellite recovery vehicle program, I thru XIV",

General Electric Missiles and Space Vehicle Department Publication PIB-52,

1960.

Back to Space History Notes

Back to Space History Notes