Jodrell Bank's role in early

space tracking activities - Part 2

Sven Grahn

Table of Contents

Part 1

- A strange new world

- The creation of the telescope

and the observatory

- How Jodrell Bank was drawn

into space tracking

- Space tracking exploits by

Jodrell Bank

- The Able program

- The U.S. Army/JPL lunar

probes

- Supporting the Able project

again

- The early Soviet Luna

probes

-

Luna 1 - whizzing past the moon - did anyone hear it?

-

Luna 2 - the first spacecraft to reach another celestial

body

-

Luna 3 - the first view of the moon's far side

Part 2

Tracking Soviet Interplanetary probes

Venera-1

After

the Soviet lunar probe launches in 1958,1959 and early 1960 (see

table of Soviet Venus probe launches) their focus shifted to planetary

flights. In October 1960 two unsuccessful Mars probe launches were made

and the Venus probe launch window that opened in early February 1961 was

also used by the Soviet Union. The first launch on 4 February failed when

the last stage of the launch vehicle was stranded in earth orbit. The ullage

rocket module (BOZ) of the fourth stage did not fire when a DC converter

supplying power to the pyro timer failed (57).

However, the second probe, Venera-1 (manufacturer's code; 1VA) smoothly

left earth orbit on 12 February 1961. We now know (55)

that objective was to hit Venus and the forward dome of the probe may have

been some sort of thermal cover, so that the probe would reach as

far down as possible while relaying data, and so that something would actually

reach the surface. Soviet media did not mention the

intention to hit Venus when they published a rather extensive description

of the probe and its mission. In the TASS statement the transmission frequency

of 922.8 MHz of the Venera 1 probe is mentioned, the first time that this

frequency was ever given as a telemetry frequency for a Soviet space vehicle.However,

the Soviet tracking network soon lost contact with the probe.

After

the Soviet lunar probe launches in 1958,1959 and early 1960 (see

table of Soviet Venus probe launches) their focus shifted to planetary

flights. In October 1960 two unsuccessful Mars probe launches were made

and the Venus probe launch window that opened in early February 1961 was

also used by the Soviet Union. The first launch on 4 February failed when

the last stage of the launch vehicle was stranded in earth orbit. The ullage

rocket module (BOZ) of the fourth stage did not fire when a DC converter

supplying power to the pyro timer failed (57).

However, the second probe, Venera-1 (manufacturer's code; 1VA) smoothly

left earth orbit on 12 February 1961. We now know (55)

that objective was to hit Venus and the forward dome of the probe may have

been some sort of thermal cover, so that the probe would reach as

far down as possible while relaying data, and so that something would actually

reach the surface. Soviet media did not mention the

intention to hit Venus when they published a rather extensive description

of the probe and its mission. In the TASS statement the transmission frequency

of 922.8 MHz of the Venera 1 probe is mentioned, the first time that this

frequency was ever given as a telemetry frequency for a Soviet space vehicle.However,

the Soviet tracking network soon lost contact with the probe.

According to a message to Jodrell Bank from Dr Alla

Massevitch the last contact with Venera 1 occurred on 17 February 1961

at 1404-1535 MT. Dr Massevitch explained in another report (53)

that the probe "was designed to transmit signals every five days. For

about 17 minutes it should have sent out an unmodulated sound, and then

transmitted coded messages giving scientific information such as temperature,

pressures, and the presence of meteorites." So, presumably, the

probe malfunctioned some time between 17 and 22 February 1961. However,

Soviet tracking stations had computed that the probe would indeed pass

near Venus and asked Jodrell Bank to try to pick up telemetry from the

probe when it passed closest to Venus on 17 May 1961. Presumably a command

to switch on the probe's transmitter was sent from the main Soviet ground

station in the Crimea. Jodrell Bank did pick up unidentified signals on

922.8 MHz on 17 May 1961 and sent them to Moscow for analysis. Obviously

nothing relating to Venera 1 had been heard since Soviet authorities never

claimed to have regained contact with the probe.

However, Soviet authorities did not lose all hope of contacting

the probe. Soviet scientists Drs Massevitch and Khodarev were invited

to Jodrell Bank by Prof. Lovell in a telegram dated 30 May 1961 and certainly

visited the observatory from 9-16 June 1961 and tried to pick up more signals

from Venera, but to no avail (53). Telegrams

from Moscow with pointing data for Venera 1 continued to be sent to Jodrell

Bank in support of this last-ditch reception attempt. The last telegram

from Moscow with pointing data for the Venera 1 probe that I could find

in the Venus probe file in the Jodrell Bank Archives is dated 20 June 1961.

Mars-1

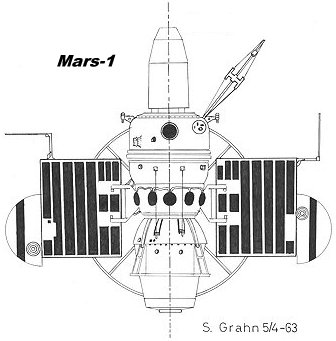

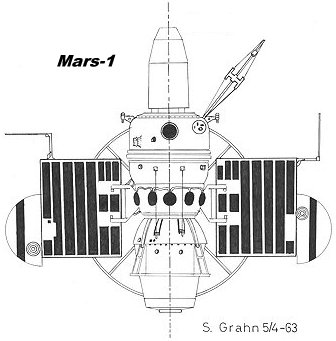

In 1962 the new space probe model designed by the Korelev

design bureau, called "Object MV" (MV for Mars-Venera), capable of being

launched to both Mars and Venus was taken into use. The first launches

of this new spacecraft took place towards Venus on 25 August, 1 September

and 12 September 1962 (See

table of Soviet/Russian Mars probe launches). The Mars launch window

opened soon after the Venus window. Two Mars versions of Korolev's "Object

MV" was prepared for launch in 1962. MV-3 for landing on Mars and MV-4

for flying past the planet. Three launch attempts were mader on 24

October, 1 November, and 4 November. The first two attempts were fly-by

probes and the last was a landing attempt. Only the middle attempt made

it out of Earth orbit, the probe launched on 1 November and called Mars-1.

Soviet

media published an extensive description of the probe's mission and its

subsystems. The radio systems were described as follows: "The craft

carries three radio systems, working on wavelengths in the metre (1.6m),

decimetre (32cm) and centimetre (5 and 8 cm) ranges....The radio complex

working in the metre range serves both for transmission of telemetric information

about condition of the station and for maintaining communication with the

earth in the event of abnormal functioning of the orientation system."

(52)An

interpretation of this description can be found in Radio

Systems of Soviet Mars and Venus Probes.

Soviet

media published an extensive description of the probe's mission and its

subsystems. The radio systems were described as follows: "The craft

carries three radio systems, working on wavelengths in the metre (1.6m),

decimetre (32cm) and centimetre (5 and 8 cm) ranges....The radio complex

working in the metre range serves both for transmission of telemetric information

about condition of the station and for maintaining communication with the

earth in the event of abnormal functioning of the orientation system."

(52)An

interpretation of this description can be found in Radio

Systems of Soviet Mars and Venus Probes.

Obviously Jodrell Bank tracked the Mars 1 probe and telegrams

giving transmitter ON times for Mars-1 and pointing data were regularly

sent to Jodrell Bank from Moscow. It was necessary for Jodrell Bank to

know when the probe's transmitters would be on because they operated for

only an hour or so a day. For example, Mars 1 transmitters would be operating

at 0850-1040 Moscow Time on 27 November 1962, at 0825-0955 Moscow Time

on 7 December 1962, and at 1700-1830 Moscow Time on 15 January 1963. Until

13 December 1962 the probe operated at regular two-day intervals between

communications session and then changed to five-day intervals (52).

Moscow even gave (44) details about the radio

systems of Mars 1: "The telemetry transmitter operates on 922.8 MHz

with +/- 120 deg phase modulation with the subcarrier frequency in the

range 1100-1700 Hz, during telemetry transmission the subcarrier frequency

is modulated in frequency by a code signal." All went well for Mars-1

for the first five months, but on 21 March 1963 all contact with the probe

was lost due to an orientation system problem. Mars-1 is estimated to have

passed Mars at a distance of 193000 km on 19 June 1863.

Zond 1 and 2

Zond 1 was launched on 2 April 1964 but no target was given

for the flight. However, most observers guessed that it was aimed at Venus.

Moscow gave technical details about the flight: On April 4 TASS described

a course correction at 1818 UT on April 3 and stated that "telemetric

information from Zond 1 is coming in on a frequency of 922.76 MHz." (51).

This revelation of the transmission frequency must have been aimed at stations

such as Jodrell Bank and the observatory successfully located the Soviet

space probe Zond 1 shortly after its launch (47).

A course correction was made on May 14 when the probe was 13 million kilometres

from the Earth (50).

An unsuccessful search with the 75 m Mark I telescope was made during the

predicted time of closest approach to Venus 17-21 July 1964 (47).

Jodrell Bank was also successful in picking up the Zond

2 probe launched to Mars on 30 November 1964. Contact with the probe was

irregular and uncertain according to (47).

This

seems to contradict a magazine report (48)

which stated that Zond 2 was received regularly by Jodrell Bank. In January

1965 and at around 2100 UT on 3,10 and 17 February 1965 signals were picked

up using the 15 meter dish at Jodrell Bank. In the same report a

visit by Soviet scientists to Jodrell Bank on 17 February 1965 is described.

Academician Keldysh was asked whether Jodrell Bank would be requested to

track any Soviet space probe in the future and replied "We shall whenever

it is necessary". On May 5, Gennadi Skuridin, on a visit to the

U.S., reported that "Transmissions from Zond 2 have stopped. We have

been unable to raise it again". (49)It

flew past Mars silently on 6 August, 1965.

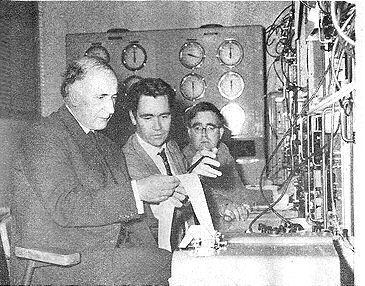

Venera 4 - Jodrell Bank tracks the

first in a series of instrumented entries in the atmosphere of another

planet

|

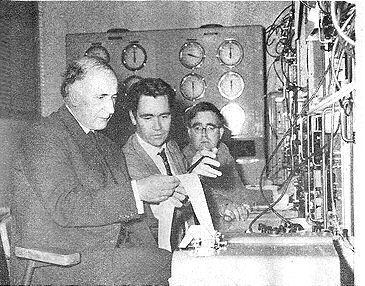

Jodrell Bank during the

tacking of Venera-4. From the left:

A.C.Bernard. Lovell, John G. Davis, Robert

Pritchard.

|

Venus probe launch attempts continued to be carried out in

1962, 1964 and 1965 (see

table of Soviet Venus probe launches) but all failed for various

reasons. In 1962 the new space probe model, designated "Object MV" (MV

for Mars-Venera), capable of being launched to both Mars and Venus was

taken into use. The first launches of this new spacecraft took place on

25 August, 1 September and 12 September 1962. The first two (model 2MV-1)

were aimed at landing a capsule on Venus and the third (model 2MV-2) was

an attempt at a fly-by of Venus. These launches all failed, leaving the

fourth stage stranded in earth orbit. One must remember that in August

1962, NASA launched Mariner 2, that flew by Venus in December 1962. The

space race was really hot! In the spring of 1964 four

more attempts at reaching Venus were made. Zond-1 was the only probe in

that series that actually headed out to Venus, but it failed before reaching

its fly-by of the planet. Another batch of five Venus attempts were made

in 1965. Two landings and two fly-bys were attempted. Only two probes reached

an interplanetary trajectory. Venera 2 did fly by Venus and Venera 3 probably

hit Venus, but the probes both failed before reaching their target.

The first space probe that reached the

surface of Venus in working condition was Venera 4. It was launched on 12

June 1967 and entered the atmosphere of Venus on 18 October 1967. The

384 kg capsule transmitted data for 94 minutes. The capsule was

crushed by atmospheric pressure at 18 bar when it was at an altitude

of 22 km experiencing an outside temperature of 274oC.

It dropped to the surface of Venus at a point near 19N 38E longitude.

Jodrell Bank tracked the

flight's approach to the surface. The observatory picked up signals from Venera

4 at 0317 UT on 18 October 1967, some

forty minutes after Venus rose above the horizon. The signals were similar

to those that Jodrell Bank had picked up in July 1967. The signal was described

(56)

as "two tone telemetry similar to the Lunik's transmissions but speeded

up four times." Doppler shift measurements were made and they showed

that the distance to venus was 30000 km at 0440 BST and the probe accelerated

along the line-of-sight with 0.3 m/s2.

The received signal strength was -140 dBm. Jodrell Bank expected, that

if the probe would orbit Venus, it would slow down and the Doppler shift

would reveal that between 0403 and 0450 UT. But, no such slowing down was

noticed, rather the opposite. the probe continued to accelerate towards

the surface and at 0415 UT the probe was estimated to have been 10000 km

form the surface. At 0438:05 UT the signals ceased, at an estimated altitude

of 100 km. Fifteen seconds later the signal re-appeared on the same frequency,

at 20 dB down and with a much reduced data rate. The Doppler shift in this

signal was very small and initially, the Jodrell Bank team thought the

capsule rested on the surface. The signals ceased finally at 0614 UT.

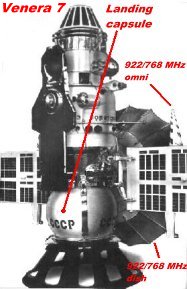

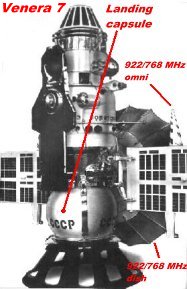

There was not enough time to redesign the next batch of

Venus probe, so Venera 5 and 6 met the same fate as Venera 4. Venera 5

survived for 53 minutes in the atmosphere and reached 26 km from

the surface. Venera 6 said to have survived to 10-12 km altitude 51 minutes

after atmospheric entry. (54) The

landing capsules of the next batch of two Venus probes launched in August

1970 were modified to survive to the surface. One probe failed to leave

Earth orbit and was given the cover name Kosmos 359. Venera 7, launched

on 17 August 1970, was equipped with a redesigned landing capsule that

could stand 180 atm and 540oC.

Radio signals appeared to stop after 35 minutes, but weak signals, 20 dB

down, were found (by post-flight signal processing) to have continued

for 23 minutes. The capsule landed at 5oS,

351o longitude. The

environment on the surface measured to be 90 +/- 15 atm, 475 +/- 20oC.

The following probe, Venera 8, launched on 27 March 1972, had a detachable

antenna to solve the previous probe's problem and worked very well. The

environment on the surface was 470 +/- 8oC,

93 atm.

Ranger tracking

Signals from the two US Moon probes Ranger 6 and Ranger 7

were received on 960 MHz using the 15 meter altitude/azimuth telescope

in conjunction with a parametric amplifier. Ranger 6 was tracked until

the moment of impact with the Moon on 2 February 1964, while Ranger 7 was

followed on 31 July 1964 until it disappeared below the western horizon

about one hour before impact. (47)

Luna 4-14, the second-generation Soviet lunar probes

It took three and a half years from the astounding success

of Luna 3 until the Soviet Union again launched a lunar probe. When these

new probes finally appeared observers assumed - correctly - that the goal

was to soft-land a probe on the moon. The new series would again thrust

Jodrell Bank into the limelight! It started with two failures, the first

on 4 January 1963 when the probe was stranded in earth orbit (1963-01A,

Sputnik 25), and the second on 2 February 1963, when the probe did not

reach orbit and fell into the Pacific These failures were not immediately

known to the public.

Luna 4,5,6,7,8 - trying again

and again to land on the moon

The first of these new Luna probes that was announced

as such was Luna 4, launched on 2 April 1963. The Soviet Union did

not ask Jodrell Bank to track the flight, but Jodrell Bank finally acquired

Luna 4 during 6 hours on 4 April after searching for it since 2 April (31).

Signals were far more complicated than those from Luna 3. On the day it

flew past the Moon (at 0124 UT at a distance of 8500 km), 6 April, signals

were recorded for 44 minutes, but there were no signs of firing of retro-rockets

at the Moon (19).  Despite

the lack of a direct request for support from the USSR, Soviet media gave

the transmission frequency - 183.6 MHz (32),

and also the traditional position fix giving a distance from the earth

at certain geocentric co-ordinates at a defined instant. This was clearly

an invitation to monitor signals in order to obtain independent confirmation

of Soviet claims. The table on the left shows the navigation fixes for

Luna 4-14 published in the official launch communiqués from TASS

(33).In

addition to the tracking reports from Jodrell Bank, the US National Security

Agency had arranged with the Naval Research Labs in Maryland to use its

45 m dish to track Luna 4. Because the flight to the moon took 88 hours

instead of 80 hours even a station as far west as on the US east coast

could pick up the signals on 183.6 MHz, which were "complicated and full

of variety"

(2). (see Luna 4-14

radio systems

for a detailed

description).

Despite

the lack of a direct request for support from the USSR, Soviet media gave

the transmission frequency - 183.6 MHz (32),

and also the traditional position fix giving a distance from the earth

at certain geocentric co-ordinates at a defined instant. This was clearly

an invitation to monitor signals in order to obtain independent confirmation

of Soviet claims. The table on the left shows the navigation fixes for

Luna 4-14 published in the official launch communiqués from TASS

(33).In

addition to the tracking reports from Jodrell Bank, the US National Security

Agency had arranged with the Naval Research Labs in Maryland to use its

45 m dish to track Luna 4. Because the flight to the moon took 88 hours

instead of 80 hours even a station as far west as on the US east coast

could pick up the signals on 183.6 MHz, which were "complicated and full

of variety"

(2). (see Luna 4-14

radio systems

for a detailed

description).

Two more launch attempts were made in 1964. The first

launch took place on 21 March and failed when he thirs stage did not reach

full thrust. The second attempt took plcae less than a month later, on

20 April 1964, when the third stage again cut off prematurely.

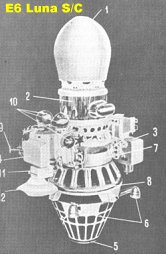

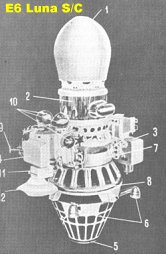

A year later, in the spring of 1965, this spacecraft series

resumed with attempts to land on the Moon - the so-called E6 probe. The

first two attempts failed. The probe launched on 12 March 1965 was left

stranded in Earth orbit as Kosmos 60, while probe launched on 10 April

never reached orbit due to a third stage failure. On 9 May Luna

5 finally was injected

into a trans-lunar trajectory. Both the new NSA station at Asmara, Ethiopia (See

article on the US

"Deep-Space

Collection"

programme), and Jodrell Bank tracked Luna 5 which transmitted

similar telemetry to that from Luna 4. The Asmara station intercepted "both

of the two spacecraft signals several times during the mission, and both

Asmara and Jodrell Bank were listening during the final approach to the

moon" (2). Two signals - indeed! 183.6

MHz and what other frequency? 922.7 MHz? However, the Doppler measurements

made at Jodrell Bank revealed no signs of retro-rocket firing from Luna

5 (20). Luna 6 was

launched on 8 June 1965, but the course-correction was not turned off correctly

on 9 June causing the probe to miss the Moon by 161000 km and enter heliocentric

orbit. Luna 7 was launched on 4 October 1965. From observations

made at Jodrell Bank (20) it was conclude

that the retrorockets of Luna 7 were in operation during the period 2058-2104

UT on 7 October 1965. However, this turned out to be wrong. According to

what we know now (61) the retro-rocket

never fired because the earth sensor lost lock just before ignition. The

probe crashed into the Moon at 2208.24 UT. Luna 8 was launched on

3 December 1965, but thus time the retrorockets fired too late. Signals

received at Jodrell Bank from Luna 8 ceased at 2151.32 UT on 6 December

1965 (21), which we now know was the moment

of impact. The retro-rocket did not ignite.

Luna

9 - the first landing on the moon

Luna

9 - the first landing on the moon

The tracking of Luna 9 was to become Jodrell Bank's most

spectacular, dramatic, and controversial appearance in the media. Luna

9 was launched from Baikonur on 31 January 1966 and was immediately

recognized by all observers as another Soviet attempt to land an instrument

package on the moon. The moon rose at Jodrell Bank on 3 February 1966 at

1333 UT. Signals from Luna 9 were received starting at 1629 UT until landing

at 1845 UT. After a few minutes of silence the signal reappeared. Ten minutes

later it changed character and the signal was recognized as facsimile because

it was similar to signals used in transatlantic transmissions experiments

using the Echo II balloon satellite (27).When

I visited Jodrell Bank in September 1967 the public affairs officer, Reginald

Lascelles, explained that he had been the person identifying the

signal as being facsimile, because of this previous employment in newspapers

where he had heard the characteristic sound of facsimile signals! Be that

as it may - someone recognized the signal as facsimile!

The pictures from Luna 9 were received on 4 February 1966

at 1530-1655 UT and again on 5 February at 1640-1740 UT. Other facsimile

transmissions were received on 3,4 and 6 February "which we have not seen

as photos" (22) . Jodrell Bank recorded

long series of telemetry bursts, each lasting six minutes and corresponding

to one picture (23). The international

facsimile standard is that the White/black transition corresponds to a

a change in audio frequency between 1.5 to 2.3 kHz, while the Luna 9 transmissions

used a change from 1.2 to 2.0 kHz. The difference in horizontal/vertical

ratio was sometimes given as a factor 2 and sometimes as a factor 2.5 .

The picture signals were transmitted on a subcarrier with maximum deviation

of 2 kHz. The synchronization signal for the pictures (start of each line?)

was a tone with the frequency 1.1 kHz (24).

The lunar panoramas consisted of vertical lines with 500 elements (each

3.6 minutes of arc wide) and the 360 degree view around the horizon consisted

of 6000 such lines (25). Jodrell Bank

recorded the Luna 9 pictures on a Mincom CM-110 tape

recorder (62) .

The fact that Jodrell Bank used a standard facsimile receiver

(borrowed from the Daily Express in Manchester) to print the pictures coming

in from the moon and did not recognize that the horizontal/vertical ratio

did not conform to the international standard led to an exchange of harsh

words with Soviet Academy of Sciences. Naturally, the Soviet authorities

would have liked to publish the pictures at their own initiative and used

the fact that the pictures published by Jodrell Bank were not quite correct

as a pretext for complaining about about the premature release of the pictures.

Prof. Lovell defended himself by pointing out the great general interest

of the pictures from moon and that the pictures still showed the correct

qualitative characters of the lunar surface. This conflict with Soviet

authorities is not only evident from public exchanges, but also from correspondence

in the Jodrell Bank Archives where I found a letter (43)

from the Academy of Sciences of the USSR complaining about the "hurried

publication of the Luna 9 pictures" by Jodrell Bank.

Incredibly,

just as in the case of Luna 2 there were disbelievers that asked Jodrell

Bank for proof of this latest Soviet feat. Thus, The "Anti-Communist League

of America, Inc." (Carrying the text: "Communism must be destroyed" in

its letterhead) wrote (26) to request

information about the descent phase of Luna 9. In reply, they received

a reprint of the article in Nature about Jodrell Bank's reception of signals

from Luna 9 (28).

Incredibly,

just as in the case of Luna 2 there were disbelievers that asked Jodrell

Bank for proof of this latest Soviet feat. Thus, The "Anti-Communist League

of America, Inc." (Carrying the text: "Communism must be destroyed" in

its letterhead) wrote (26) to request

information about the descent phase of Luna 9. In reply, they received

a reprint of the article in Nature about Jodrell Bank's reception of signals

from Luna 9 (28).

Luna 10, 11, and 12 - shifting

the focus to lunar orbit

When Luna 9 had succeeded in landing on the moon, the

Soviet focus immediately shifted to putting a probe into orbit around the

moon. In February 1966, Kosmos 111,a failed lunar probe was launched [give

details about reason for failure and details such as HF frequency]. Another

attempt, this time successful, was made on 31 March 1966, when Luna 10

was launched. Jodrell Bank successfully tracked the probe, detected its

insertion into lunar orbit and measured its period (35).

Other tracking stations, such as the Bochum Space Observatory in Germany,

also picked up the probe, including the transmission of the tune "The

International" (38 kB mp3) at 1944-1950 UT on

3 April 1966 (34) . This transmission was

made to celebrate the 23 rd Congress of the CPSU. The two following probes

in the E6 Luna series were also orbiters. The character of Luna 11

has been hotly debated and some authors think that Luna 11 was similar

to Luna 10, i.e. it had a non-stabilized orbiter, while other space historians

think it was similar to Luna 12, which did not separate a payload in lunar

orbit and actually produced pictures of the moon. The only evidence, although

inconclusive, as to the character of Luna 11 found in the Luna 11 archives

is a statement (36) by Prof. Lovell explaining

that "we received facsimile signals for a short time from Luna 11 which

appeared to be of identical form to those transmitted by Luna 9. However,

it proved impossible to make anything of the information."

I found nothing about Luna 12 in the Jodrell Bank Archives.

Perhaps this was due to the fact that special measures were taken to ensure

that Jodrell Bank would not be able to repeat its Luna-9 scoop during the

Luna-12 mission (59 p. 46). One option considered

was to gradually send back the pictures during the brief windows that Luna-12

was only within range of the Crimea, which could pick up the spacecraft

three hours before it entered Jodrell Bank’s radio visibility zone. However,

in that mode "it would have taken months" for the pictures to trickle

down to Earth. Another solution was found, enabling the Russians to send

back the pictures in 24 hours, while still leaving Jodrell Bank empty-handed.

As one of the Lavochkin bureau veterans explained : “We were able to

send back information in two bands, the metre and decimetre bands, and

to quickly switch from one band to the other, while Jodrell Bank needed

about a day to reconfigure its equipment [for this] ... That is the way

we worked : we made full use of the [three hour Soviet window] and then,

as the probe came within range of Jodrell Bank, began alternating between

the two modes in varying sequences, playing cat and mouse with Jodrell

Bank. We successfully completed our nearly round-the-clock work to send

back the images and breathed a sigh of relief. It was as if a great weight

had been lifted from our shoulders." (59)

Luna 13 and 14

After

Luna 12 The Soviet union launched a second lunar lander, Luna 13,

equipped with several new devices, including a device to measure the hardness

of the lunar surface. Jodrell Bank tracked Luna 13 and received images

in the same fashion as from Luna 9. The final launch

in this series occurred almost 18 months later, on 7 April 1968. It was

Luna

14 and pictures of the Luna 12 probe (which it probably resembled)

show a conical antenna obviously intended for the standard 768/922 MHz

TT&C system. It has been reported that Luna 14 was a test of various

subsystems for the next generation of Luna probes, including the drive

system for the Lunokhod lunar rovers. There is a message (45)

in the Jodrell Bank Archives to professor Lovell while he was in the U.S.

that the observatory had picked up Luna 14: "PLEASED TO INFORM YOU SIGNALS

FROM LUNAR ORBITER 14 RECEIVED.". Of course the telegramme refers to

Luna 14.

After

Luna 12 The Soviet union launched a second lunar lander, Luna 13,

equipped with several new devices, including a device to measure the hardness

of the lunar surface. Jodrell Bank tracked Luna 13 and received images

in the same fashion as from Luna 9. The final launch

in this series occurred almost 18 months later, on 7 April 1968. It was

Luna

14 and pictures of the Luna 12 probe (which it probably resembled)

show a conical antenna obviously intended for the standard 768/922 MHz

TT&C system. It has been reported that Luna 14 was a test of various

subsystems for the next generation of Luna probes, including the drive

system for the Lunokhod lunar rovers. There is a message (45)

in the Jodrell Bank Archives to professor Lovell while he was in the U.S.

that the observatory had picked up Luna 14: "PLEASED TO INFORM YOU SIGNALS

FROM LUNAR ORBITER 14 RECEIVED.". Of course the telegramme refers to

Luna 14.

Tests of a Soviet piloted circumlunar spacecraft - Zond

4-8

Launches in 1967

The Zond designation was confusingly used also for the

series of Soviet space vehicles that tested a manned circumlunar spacecraft.

Perhaps the intention was to be able to hide the true nature of these craft

in the case the program failed. The first two test launches of these Zond

craft (see "The

continuing enigma of Kosmos 146 and Kosmos 154") were mainly tests

of the propulsion system needed to leave earth orbit. Kosmos 146 seems

to have been partially successful, while Kosmos 154 was a failure because

the ullage rockets needed to restart the last stage of the Proton launch

vehicle were discarded prematurely. During the second half of 1967 the

Soviet Union made extensive efforts to launch the first "full-up" unpiloted

test of the Zond circumlunar mission. After several attempts in August

and September the launch finally occurred at 1907:59 UT on 22 November

1967 (42). Analysis (see "Mission

profiles of 7K-L1 flights") shows that this launch was aimed at

the moon, but the launch failed due to a second stage engine failure.

Zond 4 and the launch attempt

in April 1968

The next launch, of Zond 4, took place at 1828 UT on 2

March 1968 and, strangely, it was launched on an elliptical orbit

away from the moon. [Explain fate]. It is unclear if Jodrell Bank tracked

this flight. Russian media were very reticent concerning this flight. The

next launch attempt in the Zond program occurred very soon after Zond 4.

A Zond was launched in the direction of the moon at 2301:57 UT on

22 April 1968 (42). This flight also failed

because premature cutoff of the second stage due to a short

circuit.

Zond 5 - a strange Soviet game

of hide-and-seek and voices from the sky

The next launch took place after the summer of 1968 when

Zond 5 was sent on a circumlunar trajectory in September. Jodrell Bank

certainly  tracked

this flight, but antenna pointing angles in all probability did not come from

the Russians, but rather from the

U.S. Deep-Space Collection Programme

. From press reports we know that Jodrell

Bank intercepted signals, including voice signals uplinked to the spacecraft

from Yevpatoria and returned by the spacecraft to simulate the presence

of a cosmonaut. These Zond spacecraft did not transmit in intermittent

communications sessions as the Luna probes, but instead their transmitters

were operating continuously on 922.76 MHz. (See

Zond 4-8 radio systems) In the case of Zond 5, Soviet authorities

played a bizarre game of cat-and-mouse with the media, initially denying that

the spacecraft was going to the moon:

tracked

this flight, but antenna pointing angles in all probability did not come from

the Russians, but rather from the

U.S. Deep-Space Collection Programme

. From press reports we know that Jodrell

Bank intercepted signals, including voice signals uplinked to the spacecraft

from Yevpatoria and returned by the spacecraft to simulate the presence

of a cosmonaut. These Zond spacecraft did not transmit in intermittent

communications sessions as the Luna probes, but instead their transmitters

were operating continuously on 922.76 MHz. (See

Zond 4-8 radio systems) In the case of Zond 5, Soviet authorities

played a bizarre game of cat-and-mouse with the media, initially denying that

the spacecraft was going to the moon:

"What happened at the moon

at 0455 UT this morning[18 Sept 1969]? The head of the Jodrell Bank observatory

in England, professor Bernard Lovell, says that a Soviet spacecraft rounded

the moon and started on its way back to earth at that time. A few hours

later this report was denied by a spokesman of the foreign office

in Moscow. The report does not agree with facts, he said. At Jodrell bank,

engineers monitored signals all night from a spacecraft near the moon.

They heard signals regularly at 40 minute intervals. At 0455 UT this morning

they found that the spacecraft had circumnavigated the moon at a minimum

distance of 1500 km. The craft then headed back to earth along an elliptical

trajectory. No retrorockets were fired...." (40)

After

Zond 5 had passed the moon there were more surprises in store for those

monitoring the flight at Jodrell Bank: "On the night of 19-20 September,

the craft was clearly observed by Jodrell Bank to be on the return swing

and a Russian voice, presumably tape-recorded, was heard calling out instrument

values, as though communications were being tested for a subsequent manned

mission." (39). It turned out that

such voice signals were also picked up by the Bochum space observatory

(41).

According to the observatory's director, Heinz Kaminski, the voice had

been either sent from Earth to the spacecraft or the other way by means

of a tape recorder.

After

Zond 5 had passed the moon there were more surprises in store for those

monitoring the flight at Jodrell Bank: "On the night of 19-20 September,

the craft was clearly observed by Jodrell Bank to be on the return swing

and a Russian voice, presumably tape-recorded, was heard calling out instrument

values, as though communications were being tested for a subsequent manned

mission." (39). It turned out that

such voice signals were also picked up by the Bochum space observatory

(41).

According to the observatory's director, Heinz Kaminski, the voice had

been either sent from Earth to the spacecraft or the other way by means

of a tape recorder.

On Friday 20 September, TASS finally ended the bizarre

hide-and-seek and announced that Zond 5 had passed within 1950 km of the

moon's surface at 0440 UT on 18 September and was heading back to earth.

(See table below for a complete timeline of the Zond 5 flight). The flight

ended on 21 September 1968. Jodrell Bank lost contact at 1500 UT on 21

September 1968 when the spacecraft was 80000 km from earth. The descent

vehicle separated at 1530 UT and re-entry started at 1554 UT. The radio

black-out period ended at 1558 UT and splashdown occurred at 1608 UT in

the Indian Ocean off Madagascar.

Zond 6 - a dress rehearsal

that went wrong?

Zond 6 was launched at 1911:31 UT on 10 November 1968,

rounded the Moon at a distance of 2420 km on 14 November and on 17 November

it made a skip-lob re-entry into Soviet airspace. Howeveer, the re-entry

capsule crashed to the ground because of a faulty parachute, but the pictures

take at the Moon could be rescued and published. In this way the flight

was erroneously regarded by many Western observers as a complete success

leading up to a piloted circumlunar flight within short. Very little information

about Jodrell Banks' tracking of Zond 6 can be found in the Jodrell Bank

Archives, but they do contain the typed text of a statement to the press

dated 14 November 1968: Zond 6 passed behind the Moon from 0350 to 0420

a.m. (given as 0250-0320 UT in (37).

) at a distance similar to that of Zond 5, that is between 1000 and

2000 miles. There was no guidance or firing of retrorockets and the Zond

now appears to be on its return journey to earth. Tracking is continuing

until the probe sets early this afternoon and will be resumed tonight.

The only other document about the Zond flights found in the "lunar probes"

file of the Jodrell Bank Archives is a letter from Prof. Lovell to Prof.

DWR Wilson, University of Alberta, dated 27 November 1968 in which he explained

that "...Zond 5 and 6 set below our horizon several hours before re-entry.."

Zond 7

In August 1969, a few weeks after the flight of Luna 15

and Apollo 11, the Soviet Union launched the next Zond flight, but it was

still unmanned. It was the first, and as it turned out, only really successful

flight in the Zond series. Jodrell Bank tracked the flight and informed

the media that Zond 7 also transmitted voice communications, and that signals

were much stronger than those from Zond 6 (38).

We now know that yhis observation is explained by the fact that the high-gain

antenna on Zond-6 did not deploy, while it apparently did on Zond-7. (60).

Luna 15-24

Perhaps

the monitoring of these Soviet attempts to beat the Apollo programme by

a series of unmanned lunar probes was Jodrell Bank's last major public

appearance as a space tracking station. Luna 15, the

first attempt to "beat" Apollo, was launched three days ahead of Apollo

11 and the media immediately saw a drama unfolding: The unmanned Soviet

lunar probe with an unknown mission - but probably a lunar sample return

- and the first attempt at a a manned lunar landing.

Perhaps

the monitoring of these Soviet attempts to beat the Apollo programme by

a series of unmanned lunar probes was Jodrell Bank's last major public

appearance as a space tracking station. Luna 15, the

first attempt to "beat" Apollo, was launched three days ahead of Apollo

11 and the media immediately saw a drama unfolding: The unmanned Soviet

lunar probe with an unknown mission - but probably a lunar sample return

- and the first attempt at a a manned lunar landing.

Jodrell Bank again came to play a major role in monitoring

the flight and in interpreting the flight events to the general public.

Professor Lovell noted that the probe was on a "slow" trajectory to the

Moon, taking a day longer to reach the Moon that previous Luna flights.

On July 17, as Luna 15 entered lunar orbit, Jodrell

Bank reported that the signals from Luna 15 "are of an entirely new

type never heard before." (46)

It is hard to know if this means that Jodrell Bank had never before tracked

a Luna probe on 922.8 MHz (which we know was used by Luna 15) or that the

telemetry format was much different (See Radio

Systems used by the Luna 15-24 series of spacecraft). At this time

Jodrell bank was co-operating closely with the US Deep Space Collection

effort and this organization may have helped Jodrell Bank find the correct

frequency and location the spacecraft in the sky. However,

Jodrell Bank provided the news about the final phase of the Luna 15 drama

in a news release:

However,

Jodrell Bank provided the news about the final phase of the Luna 15 drama

in a news release:

"Signals ceased at 4.50 p.m. this evening

[1550 UT on 21 July 1969; Soviet news releases gave the time as 1551 UT].

They have not yet returned. The retrorockets were fired at 4.46 p.m. [1546

UT; Soviet news releases gave the time as 1547 UT] on the 52nd orbit and

after burning for 4 minutes the craft was on or near the lunar surface,

The approach velocity was 480 km/h [presumably determined by measuring

the Doppler shift] and it is unlikely of anything could have survived."

There was a bizarre incident during the flight. In the U.S.

the notion was raised that Luna 15 could possibly interfere with Apollo

11 in some way. NASA let Frank Borman, commander of Apollo 8, approach

the Soviet Academy of Sciences to find out if there was any risk of radio

interference to Apollo 11 from Luna 15 operations near the Moon. The Soviets

replied and it seems that the frequency 115 MHz was raised in this exchange.

Suppose Luna 15 had worked perfectly, would it have beaten

Apollo to returning the first lunar samples to earth? By using the flight

profiles of Luna 16,20 and 24 one can deduce that Luna 15 could have returned

to earth 12.44 days after launch. This would be July 25.565 (i.e. at 1334

UT on July 25, almost a day after the splashdown of Apollo 11, which took

pace at 1635 UT on 24 July! So, Apollo 11 would not have been beaten anyway!

Even if Luna 15 had been able to stick to the quickest return flight schedule

(that of Luna 16) it would have been back after 11.65 days, i.e. at 0100

UT on 25 July - even this after the return of Apollo 11!

Jodrell Bank and public opinion about the space race

Sir Bernard often spoke out openly about his opinion of various

space missions. In particular his comments that Apollo 8 contributed very

little to astronomy was misinterpreted. To the knowledgeable person his

statement is obviously true, but it was interpreted as a criticism of the

Apollo program in general. As an example of how the public reacted to Sir

Bernard's refreshing outspokenness is the following extract from a letter

from Mary N. Allen, 1441 Montgomery Street, apartment 6, San Francisco,

California, dated 30 December 1968: ".....I think you should recognize

that for millions of people around the world (not, I gather, excluding

many in the U.K.) you are the epitome of all that is bogus, washed up and

unscientific in weak, wobbling Old Britain. After, and usually before each

"space occasion", your silly, ignorant and often gushing utterances call

forth this awareness anew. ..."

References and Notes

-

Bernard Lovell, "Astronomer by

Chance", McMillan Books, London, 1991, ISBN 0-333-55195-8

-

James D. Burke, "Seven Years to

Luna 9",: Studies in Intelligence, Summer 1966

-

James D. Burke, "The Missing

Link", Studies in Intelligence, Winter 1978

-

"Venus 4 underscores U.S. delay", Aviation

Week, 23 October 1967, p.26

-

V.A. Kotelnikov, .M. Dubrovin, O.N. Rzhiga and A.M.

Shakhovsky. "Reception and investigation of the properties of radio signals

from Soviet Space Rockets".

-

Hearings before the Committee on Science

and Astronautics and Special Subcommittee on Lunik Probe, U.S. House of

Representatives, Eighty-Sixth Congress, First Session, U.S. Government

Printing Office, Washington D.C., 1959. The hearings were held during the

period May 11-29, 1959.

-

Martin Caidin, "Race for the Moon". William Kimber

Publisher, London 1960.

-

The Big Red Lie, Lloyd Mallan, Fawcett

Book no 417, New York, 1959.

-

A letter from the AFBMD dated

6 May 1958

-

J.G Davies, A.C.B. Lovell, Observations

of the Russian Moon Rockets Lunik II and III, Space Research 1, Proceedings

of the first COSPAR conference, 1960.

-

Letter from Professor Lovell to Prof.

Nesmeyanov of AN USSR, 9 December 1959.

-

Asif A. Siddiqi, "First to the

Moon", Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, Vol.51, pp.231-238,

1998.

-

Leonid I Sedov, "The Orbits Of

Cosmic Rockets Towards The Moon", presented at American Rocket Society's

14 the Annual Meeting, Sheraton Park Hotel,Nov 16-20,1959. ARS paper no

1051A-59.

-

Henry G. Plaster, "Snooping

on Space Pictures", Studies in Intelligence, Fall 1964.

-

"The Other Side of the Moon", Translated

from the Russian by J.B. Sykes, Pergamon Press, 1960.

-

A telegram from Prof. Davies

to SPACE CONN NASA WASH DC dated 8 October 1959. The telegram concluded

"RUSSIAN

PREDICTIONS FOR OCT 9 FOLLOW".

-

Swedish Daily Expressen for

Monday, 19 October 1959, p. 12: "Lunik saw 2/3 of the moon's far side"

-

Swedish Daily Expressen for

Tuesday, 27 October 1959, centre spread: "Pictures from space: the far

side of the moon".

-

A letter from Prof. Lovell to Brian

Harvey, dated 22 February 1966.

-

A letter from Prof. Lovell to Martin

Postranecky, Prague, dated 9 November 1965.

-

A letter from Prof. Lovell to Martin

Postranecky, Prague, dated 21 June 1966.

-

A letter from Prof. Lovell to E.M.

Shoemaker dated 11 February 1966.

-

A transcript of a seminar on Jodrell

Bank's reception of pictures from Luna 9 written by Eugene M Shoemaker

-

A letter from Prof. Lovell to E.M.

Shoemaker dated 6 April 1966.

-

A message from M Keldysh at

the Academy of Sciences of USSR

-

A letter from John Crippen,

Executive Secretary of "The Anti-Communist League of America, Inc."

dated 5 March 1966.

-

A telegram from Prof. Lovell to SATREV

NY (newspaper?)

-

J.G. Davies, Sir Bernard Lovell,

R.S. Pritchard, F.G. Smith, "Observations of the Russian Moon probe

Luna 9", Nature, February 26, 1966, pp. 848-850.

-

A telegram to SPACE CONN NASA WASH

DC dated 7 October 1959

-

Second telegram to SPACE CONN NASA

WASH DC from J.G. Davies dated 7 October 1959

-

"Lunik 4 believed to have failed in

Mission", Aviation Week & Space Technology, 15 April, 1963, p.38.

-

"Soviets Launch Lunik 4", Aviation

Week & Space Technology, 8 April, 1963, p.38.

-

Mastery of Cosmic Space by the USSR,

official TASS communiqués and materials from the central press 1957-1967,

Nauka Publishers, Moscow 1971.

-

A letter from Mr Heinz Kaminski,

of the Bochum Space Observatory in Germany, dated 30 September 1966, congratulating

Prof. Lovell on the Luna 9 success and attaching data from Bochum's observations

of Luna 10 during the period 3-5 May 1966.

-

A letter to Hans Schnabel dated

17 June 1966 Prof. Lovell wrote that "We made measurements on Luna 10

only during the first few days of its career". He goes on to note that

Jodrell Bank determined the orbital period to be 3 hours.

-

A letter to William Pickering,

director of NASA JPL, dated 30 September 1966.

-

Geoff Perry, day-to-day

log, entry for 10 November 1968.

-

Geoff Perry, day-to-day

log, entry for 12 August 1969.

-

K.W Gatland, "Robot Explorers"

-

Swedish Daily Expressen for

Wednesday, 18 September 1968: "Spacecraft rounded the moon. Who launched

it?"

-

Swedish Daily Expressen for

Friday, 20 September 1968, quoting a Reuters telegram.

-

Issue No. 10, 1998 of the Russian

magazine Novosti Kosmonavtiki

-

Letter to professor Lovell from

Mstislav Keldsyh of AN USSR dated 26 February 1966.

-

A telegram to Jodrell Bank from

Akademi Nauk in Moscow dated 10 January 1963 gave details about the

radio systems of Mars 1. The telegram was in Russian, but the Cyrillic

characters were transcribed in latin letters. Dr Stas Barabash at the Swedish

institute of Space Physics in Kiruna has helped me translate this telegram.

-

A telegram dated 10 April 1968

sent to "LOVELL WESBUROHOTEL NY" by R Pritchard.

-

Brian Harvey, The New Russian

Space Programme, John Wiley & Sons, 1996, p.130.

-

The COSPAR bulletin for 1964

(date unknown, I have only kept the relevant pages)

-

Flight International, 25 February

1965, "Jodrell Bank Tracks Zond 2".

-

Flight International, 20 May

1965

-

Flight International, 28 May

1964, "Zond 1 changes course".

-

Flight International, 9 April

1964, "Soviet probe heading for Venus?".

-

Pravda, 15 December 1962,

"First flight to Planet Mars".

-

Flight International, 22

June 1961, "Venus Probe Remains Silent".

-

Donald F Robertson, "Venus

- A prime Soviet Objective", Spaceflight, May 1992, pp.158-161.

-

Timothy Varfolomeyev, "The

Soviet Venus Programme",Spaceflight, February 1993, pp.42-43.

-

Nature, Vol. 216, October

28, 1967, p.321, "Landing on Venus".

-

Timothy Varfolomeyev,

" Soviet Rocketry that Conquered Space, Part 5, The First Planetary Probe

Attempts, 1960-64",Spaceflight, March 1998, pp.85-88.

-

Bernard Lovell, 'The Moon Match',

in "Summer Days"edited by M Meyer, Eyre & Methuen, London 1981, pp

123-131

-

Biography of Babakin published

in 1996.

-

Hendrickx, Bart, "The Kamanin

Diaries 1967-1968", JBIS Vol 53 No 11/12, Nov/Dec 2000, p.415

-

Hendrickx, Bart, Siddiqi, Asif,

Varfolomeyev, Timothy, "The tough road travelled: A new look

at the second generation Luna probes", JBIS, Vol. 53, 9/10, Sept/Oct 2000,

p. 340

- Mincom, a

now now-defunct division of 3M, which specialized in magnetic

tape recorders for instrumentation and sound recording.

Back

to Part 1

Back

to Part 1

Back

to Space Tracking Notes

Back

to Space Tracking Notes

Soviet

media published an extensive description of the probe's mission and its

subsystems. The radio systems were described as follows: "The craft

carries three radio systems, working on wavelengths in the metre (1.6m),

decimetre (32cm) and centimetre (5 and 8 cm) ranges....The radio complex

working in the metre range serves both for transmission of telemetric information

about condition of the station and for maintaining communication with the

earth in the event of abnormal functioning of the orientation system."

(52)An

interpretation of this description can be found in Radio

Systems of Soviet Mars and Venus Probes.

Soviet

media published an extensive description of the probe's mission and its

subsystems. The radio systems were described as follows: "The craft

carries three radio systems, working on wavelengths in the metre (1.6m),

decimetre (32cm) and centimetre (5 and 8 cm) ranges....The radio complex

working in the metre range serves both for transmission of telemetric information

about condition of the station and for maintaining communication with the

earth in the event of abnormal functioning of the orientation system."

(52)An

interpretation of this description can be found in Radio

Systems of Soviet Mars and Venus Probes.

After

the Soviet lunar probe launches in 1958,1959 and early 1960 (see

table of Soviet Venus probe launches) their focus shifted to planetary

flights. In October 1960 two unsuccessful Mars probe launches were made

and the Venus probe launch window that opened in early February 1961 was

also used by the Soviet Union. The first launch on 4 February failed when

the last stage of the launch vehicle was stranded in earth orbit. The ullage

rocket module (BOZ) of the fourth stage did not fire when a DC converter

supplying power to the pyro timer failed (57).

However, the second probe, Venera-1 (manufacturer's code; 1VA) smoothly

left earth orbit on 12 February 1961. We now know (55)

that objective was to hit Venus and the forward dome of the probe may have

been some sort of thermal cover, so that the probe would reach as

far down as possible while relaying data, and so that something would actually

reach the surface. Soviet media did not mention the

intention to hit Venus when they published a rather extensive description

of the probe and its mission. In the TASS statement the transmission frequency

of 922.8 MHz of the Venera 1 probe is mentioned, the first time that this

frequency was ever given as a telemetry frequency for a Soviet space vehicle.However,

the Soviet tracking network soon lost contact with the probe.

After

the Soviet lunar probe launches in 1958,1959 and early 1960 (see

table of Soviet Venus probe launches) their focus shifted to planetary

flights. In October 1960 two unsuccessful Mars probe launches were made

and the Venus probe launch window that opened in early February 1961 was

also used by the Soviet Union. The first launch on 4 February failed when

the last stage of the launch vehicle was stranded in earth orbit. The ullage

rocket module (BOZ) of the fourth stage did not fire when a DC converter

supplying power to the pyro timer failed (57).

However, the second probe, Venera-1 (manufacturer's code; 1VA) smoothly

left earth orbit on 12 February 1961. We now know (55)

that objective was to hit Venus and the forward dome of the probe may have

been some sort of thermal cover, so that the probe would reach as

far down as possible while relaying data, and so that something would actually

reach the surface. Soviet media did not mention the

intention to hit Venus when they published a rather extensive description

of the probe and its mission. In the TASS statement the transmission frequency

of 922.8 MHz of the Venera 1 probe is mentioned, the first time that this

frequency was ever given as a telemetry frequency for a Soviet space vehicle.However,

the Soviet tracking network soon lost contact with the probe.

Despite

the lack of a direct request for support from the USSR, Soviet media gave

the transmission frequency - 183.6 MHz

Despite

the lack of a direct request for support from the USSR, Soviet media gave

the transmission frequency - 183.6 MHz

Incredibly,

just as in the case of Luna 2 there were disbelievers that asked Jodrell

Bank for proof of this latest Soviet feat. Thus, The "Anti-Communist League

of America, Inc." (Carrying the text: "Communism must be destroyed" in

its letterhead) wrote

Incredibly,

just as in the case of Luna 2 there were disbelievers that asked Jodrell

Bank for proof of this latest Soviet feat. Thus, The "Anti-Communist League

of America, Inc." (Carrying the text: "Communism must be destroyed" in

its letterhead) wrote  After

Luna 12 The Soviet union launched a second lunar lander, Luna 13,

equipped with several new devices, including a device to measure the hardness

of the lunar surface. Jodrell Bank tracked Luna 13 and received images

in the same fashion as from Luna 9. The final launch

in this series occurred almost 18 months later, on 7 April 1968. It was

Luna

14 and pictures of the Luna 12 probe (which it probably resembled)

show a conical antenna obviously intended for the standard 768/922 MHz

TT&C system. It has been reported that Luna 14 was a test of various

subsystems for the next generation of Luna probes, including the drive

system for the Lunokhod lunar rovers. There is a message

After

Luna 12 The Soviet union launched a second lunar lander, Luna 13,

equipped with several new devices, including a device to measure the hardness

of the lunar surface. Jodrell Bank tracked Luna 13 and received images

in the same fashion as from Luna 9. The final launch

in this series occurred almost 18 months later, on 7 April 1968. It was

Luna

14 and pictures of the Luna 12 probe (which it probably resembled)

show a conical antenna obviously intended for the standard 768/922 MHz

TT&C system. It has been reported that Luna 14 was a test of various

subsystems for the next generation of Luna probes, including the drive

system for the Lunokhod lunar rovers. There is a message  tracked

this flight, but antenna pointing angles in all probability did not come from

the Russians, but rather from the

tracked

this flight, but antenna pointing angles in all probability did not come from

the Russians, but rather from the

After

Zond 5 had passed the moon there were more surprises in store for those

monitoring the flight at Jodrell Bank: "On the night of 19-20 September,

the craft was clearly observed by Jodrell Bank to be on the return swing

and a Russian voice, presumably tape-recorded, was heard calling out instrument

values, as though communications were being tested for a subsequent manned

mission."

After

Zond 5 had passed the moon there were more surprises in store for those

monitoring the flight at Jodrell Bank: "On the night of 19-20 September,

the craft was clearly observed by Jodrell Bank to be on the return swing

and a Russian voice, presumably tape-recorded, was heard calling out instrument

values, as though communications were being tested for a subsequent manned

mission."  Perhaps

the monitoring of these Soviet attempts to beat the Apollo programme by

a series of unmanned lunar probes was Jodrell Bank's last major public

appearance as a space tracking station. Luna 15, the

first attempt to "beat" Apollo, was launched three days ahead of Apollo

11 and the media immediately saw a drama unfolding: The unmanned Soviet

lunar probe with an unknown mission - but probably a lunar sample return

- and the first attempt at a a manned lunar landing.

Perhaps

the monitoring of these Soviet attempts to beat the Apollo programme by

a series of unmanned lunar probes was Jodrell Bank's last major public

appearance as a space tracking station. Luna 15, the

first attempt to "beat" Apollo, was launched three days ahead of Apollo

11 and the media immediately saw a drama unfolding: The unmanned Soviet

lunar probe with an unknown mission - but probably a lunar sample return

- and the first attempt at a a manned lunar landing.

However,

Jodrell Bank provided the news about the final phase of the Luna 15 drama

in a news release:

However,

Jodrell Bank provided the news about the final phase of the Luna 15 drama

in a news release: