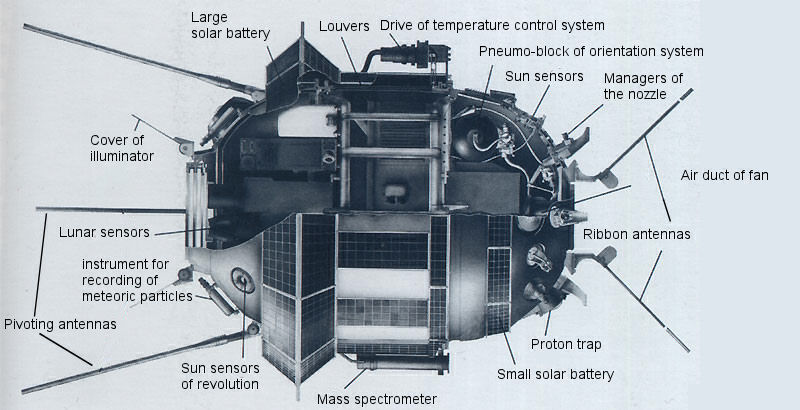

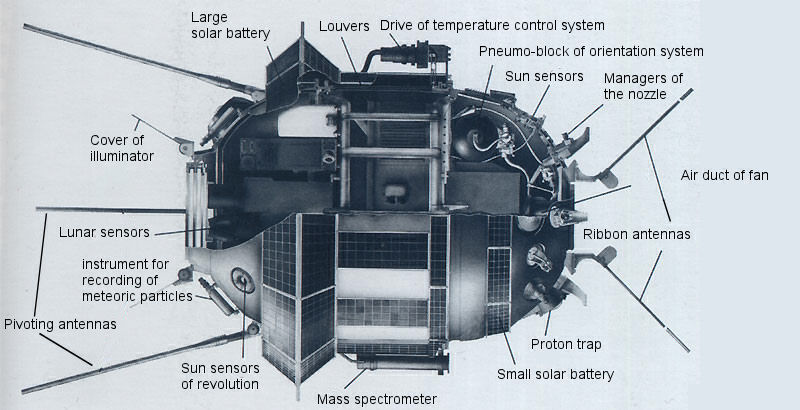

One of the origins of Luna-3 was the work by Boris Raushenbakh on attitude control started in 1955 in the NII-1 rocket research institute of the Ministry of Aviation. This work was co-ordinated with Korolev's design bureau and had as its goal stabilised photo-reconnaissance satellites. Raushenbakh's group was contracted by the lunar project section Korolev's design bureau OKB-1 to design the attitude control for the E-2 variant of lunar exploration craft intended to image the Moon's hidden side. The manager of the lunar probe project at OKB-1 was Gleb Maksimov. An excellent account of these early Soviet lunar missions can be found in (4) and (14). A cutaway sketch of the space probe with a Soviet-era translation of Russian captions added is shown below.

The radio system was designed by deputy chief designer of the NII-885 (Scientific Research Institute of Radio Instrument Building, established 1938), Yevgeniy Boguslavskiy at NII-885 and it provided trajectory measurements, telemetry and command and command verification functions. Boguslavskiy and Boris Chertok (1) (deputy chief designer at Korolev's OKB-1) preferred pulsed systems for telemetry and ranging ever since the 1940's when Boguslavskiy had criticized the German use of carrier based radio systems in their missiles. However for E-2A Boguslavskiy surprised everyone by designing a continuous carrier system. The explanation was that tried and true methods were quicker and safer to develop under a rushed schedule. Boguslavskiy later explained that the lack of contrast in the pictures from Luna-3 was caused by lack of onboard transmitter power. The low contrast of the Luna-3 images is partly due to the fact that the Moon was illuminated from above. There isn't much contrast in a full moon. The electronics of Luna-3 was transistorized, an innovation that was regarded as risky.

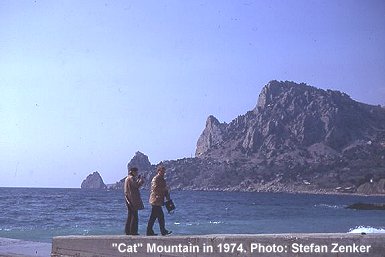

Boguslavskiy

and the NII-885 was also responsible for setting up the ground station

at

Kochka mountain near Simeiz in the Crimea in cooperation with the military

unit 32103. The station was placed on the southern slope of a mountain

facing the Black Sea. It was formally a part of NII-4 under general Sokolev

(1). The location probably had something

to do with the fact that the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory and

the Physical Institute of the USSR Academy of Sciences was, and is, located

at Simeiz. The ground station and control center had been in operation

since 23 September 1958, i.e the same day that the very first Soviet attempt

to reach the moon was made (14).

Boguslavskiy

and the NII-885 was also responsible for setting up the ground station

at

Kochka mountain near Simeiz in the Crimea in cooperation with the military

unit 32103. The station was placed on the southern slope of a mountain

facing the Black Sea. It was formally a part of NII-4 under general Sokolev

(1). The location probably had something

to do with the fact that the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory and

the Physical Institute of the USSR Academy of Sciences was, and is, located

at Simeiz. The ground station and control center had been in operation

since 23 September 1958, i.e the same day that the very first Soviet attempt

to reach the moon was made (14).

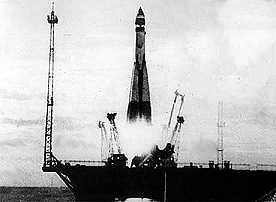

The

E-2A probe was sent to Tyuratam in August 1959 even though it was not ready

for flight. Final testing would be performed at the launch site. Chertok

traveled to the launch site on 17 September and the probe was declared

ready for launch on 25 September (1). In

the small hours of 4 October 1959, a mere two years after the launch of

Sputnik, the Soviet Union launched its most impressive space spectacular

ever - Luna 3 - the first space vehicle to catch a view of the moon's hidden

far side. The E-2A probe weighing 278.5 kg lifted off at 0043:39 UT on

an 8K72 rocket from Baikonur. The space probe was placed in an earth orbit

with perigee at 48280 km, apogee at 468300 km and an inclination to the

equator of 55 degrees (5). During its flight,

that lasted until 29 April 1960 when it decayed in the Earth's atmosphere,

Luna 3 was to bring credit to its creators and put the British Jodrell

Bank radio telescope into the media focus.

The

E-2A probe was sent to Tyuratam in August 1959 even though it was not ready

for flight. Final testing would be performed at the launch site. Chertok

traveled to the launch site on 17 September and the probe was declared

ready for launch on 25 September (1). In

the small hours of 4 October 1959, a mere two years after the launch of

Sputnik, the Soviet Union launched its most impressive space spectacular

ever - Luna 3 - the first space vehicle to catch a view of the moon's hidden

far side. The E-2A probe weighing 278.5 kg lifted off at 0043:39 UT on

an 8K72 rocket from Baikonur. The space probe was placed in an earth orbit

with perigee at 48280 km, apogee at 468300 km and an inclination to the

equator of 55 degrees (5). During its flight,

that lasted until 29 April 1960 when it decayed in the Earth's atmosphere,

Luna 3 was to bring credit to its creators and put the British Jodrell

Bank radio telescope into the media focus.

Korolev wanted that the TASS communiqué of the launch of the probe mentioned the objective of photographing the Moon's far side, but less courageous minds prevailed (1). Soviet media announced that Luna 3 transmitted signals on 39.986 MHz that consisted of pulses 0.2-0.8 seconds long sent at a repetition rate of 1 +/- 0.15 Hz. The transmitter on 183.6 MHz was also used for tracking (trajectory determination). Information from the probe was sent at intervals of 2-4 hours/day. On 4 October 1959 the transmitters were to be switched on at 1300 MT (1000 UT) to operate for two hours (until 1200 UT) at a point 108000 km over 80 degrees east and 5 degrees south. At this time everything appeared to be in good shape (1).

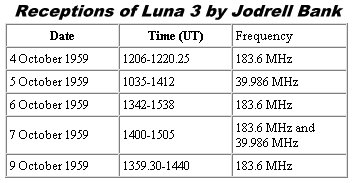

For Luna 3, the Soviet Union

again provided Jodrell Bank with pointing information for its telescope

during the Luna 3 flight. Such data were sent on 4,7,8,9 October 1959 and

on several more days in October 1959. Therefore, Jodrell Bank successfully

picked up Luna 3 less than ten hours after launch: Signals on 183.600 MHz

were received at 1206-1220.25 UT on 4 October 1959 (this agrees reasonably

well with the schedule announced by the Russians at launch - see above).

Jodrell Bank kept their colleagues at NASA up to date with its tracking

activities on a daily basis. Pointing information from the Russians were

obviously also relayed to NASA (8).

In general, observations were sent both to the USA and the USSR. All data

from the USSR were forwarded to the U.S., but not vice versa. Comprehensive

reports including tape recordings were sent to Moscow after the flight

was over. The reports to NASA were sent to the telegram address SPACE CONN

NASA WASH DC (for the attention of an individual called Bryant).

In the morning of 5 October

Chertok returned to Moscow from the launch site (1).

He returned to work in the morning of 6 October and was in a meeting about

the upcoming Venus shots when Korolev called him on the phone and told

him to "come along, bring no documents, don't count on returning home today...".

When Chertok entered his boss' room Korolev was ordering up a plane. After

hanging up he explained that

"radio contact with the probe are very

bad. Telemetry cannot be received properly and commands are not received.

We will fly to the Crimea to be there in time for the next communications

session that starts at 1600 MT (1300 UT). There are two cars at the gate.

Take one, go home, fetch what you need and then come to Vnukovo. The plane

leaves at 1200 MT (0900 UT)".

In the morning of 5 October

Chertok returned to Moscow from the launch site (1).

He returned to work in the morning of 6 October and was in a meeting about

the upcoming Venus shots when Korolev called him on the phone and told

him to "come along, bring no documents, don't count on returning home today...".

When Chertok entered his boss' room Korolev was ordering up a plane. After

hanging up he explained that

"radio contact with the probe are very

bad. Telemetry cannot be received properly and commands are not received.

We will fly to the Crimea to be there in time for the next communications

session that starts at 1600 MT (1300 UT). There are two cars at the gate.

Take one, go home, fetch what you need and then come to Vnukovo. The plane

leaves at 1200 MT (0900 UT)".

Korolev

had taken the decision in the morning after reviewing the results of the

previous day's communications session. Weak signals had been received in

5 brief periods: 1212-1221, 1227-1233, 1239-1244, 1250-1309, 1341-1409

UT (see diagram below taken from (17)).

During 5 October Jodrell Bank could not receive any signals on main telemetry

frequency, 183.6 MHz. In a message to NASA dated 5 October 1959, Jodrell

Bank described observations made on 5 October 1959 described: "Signals

received on 39.986 MHz from 1035 to 1412 UT. At 1301 UT the frequency is

fluctuating rapidly and at 1351 UT the frequency starts drifting down rapidly."

This

was the only occasion on which Jodrell bank failed to pick up the main

communications link on 183.6 MHz despite the fact that the British radio

telescope had an aperture almost ten times that of the little station in

the Crimea. Clearly there was reason for Korolev to be worried!.

To organize the hurried flight Korolev had to mobilize the air force, Aeroflot, the Communist party in the Crimea and the Soviet Council of Ministers! The flight to the Crimea was made with the most modern airliner at the time, a Tu-104 jet plane. There were six passengers on board including Korolev, Academician Keldysh, Boris Chertok and Arkaiy Ostashev (senior engineer in OKB-1) who arrived so late that the plane had to interrupt taxiing to bring him on board. The plane landed in the Crimea (probably Simferopol, although Chertok does not say so).

They were picked up by helicopter

but could not land at Ai-Petri as originally planned because of "wet snowfall"

and zero visibility. Instead they diverted to a helicopter pad at Yalta.

The SIM and Pobeda cars from the local party committee were redirected

to Yalta. The local party bigwigs wanted to take Korolev and his party

on a tour of the area, but Korolev pointed out the need to proceed immediately

to Simeiz. Korolev and his party arrived at the control center near the

"Pavlov observatory" at 1430 MT (1130 UT).

They were picked up by helicopter

but could not land at Ai-Petri as originally planned because of "wet snowfall"

and zero visibility. Instead they diverted to a helicopter pad at Yalta.

The SIM and Pobeda cars from the local party committee were redirected

to Yalta. The local party bigwigs wanted to take Korolev and his party

on a tour of the area, but Korolev pointed out the need to proceed immediately

to Simeiz. Korolev and his party arrived at the control center near the

"Pavlov observatory" at 1430 MT (1130 UT).

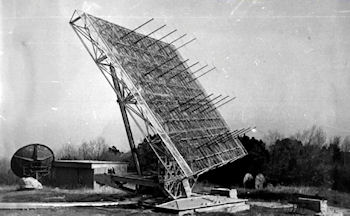

The antenna system for communicating with the probe had an aperture of 100 square meters. It consisted of an array of crossed dipoles (turnstile antennas). It was based on a U.S. SCR-627 radar antenna obatined by the Soviet Union during WWII as part of the Lend-Lease program (20 ). (see image on the right). The receiving antennas for short-wave telemetry on 19.993 MHz and 39.986 MHz (see "The radio systems of the early Luna probes") were probably also located at Kochka mountain or nearby. For 20 MHz two stacked three element Yagi antennas with a total gain of 7-10 dB, while 40 MHz was received with a crossed Yagi (to pick up the two different polarisations) using ten elements and having a gain of 13 dB. In (16) it is stated that "the receiving antennas were set up on a steep seashore". They could have been set up at Katsiveli village on the coastline below Cat Mountain wher there were also parabolic dishes for radio astronomy already in those days. These were actually used on a 176-meter as an inetferometer for measurin he angular position fo the lunar probes. The picture on the left illustrates the kind of antenna used for this purpose.

Radio equipment were housed

in trailers and the control center itself was housed in a temporary wooden

barrack. In one of the rooms was the image recording equipment where the

pictures from the moon were to be recorded on thermo-paper for real-time

readout and film, later to be developed in Moscow. The staff lived in tents

and there was a field kitchen cart steaming away among the tents. It all

gave the appearance of a military camp(1),

which it was to some extent. Koshka (Cat) mountain is located at approximately

34.02 North 44.54 East longitude. There was a back-up station located

on the Kamchatka peninsula as described vividly

in (19).

Boguslavskiy

offered the opinion that the problems the following day was caused by an

unfortunate "dip" in the antenna diagram of the probe. Korolev interviewed

the operators of the control center and found that the work of various

operators was inadequately co-ordinated and that military officers formed

a second tier of direction for the operators. Korolev now ordered that

only Boguslavskiy would direct operations during communication sessions

with the probe. At 1600 MT (1300 UT) telemetry was received and to everybody's

surprise everything worked well onboard the spacecraft. During this communications

session the probe made its closest approach to the Moon at 1416 UT on 6

October 1959 when Luna 3 passed over the lunar south pole at a distance

7884 km from the moon's centre.

Boguslavskiy

offered the opinion that the problems the following day was caused by an

unfortunate "dip" in the antenna diagram of the probe. Korolev interviewed

the operators of the control center and found that the work of various

operators was inadequately co-ordinated and that military officers formed

a second tier of direction for the operators. Korolev now ordered that

only Boguslavskiy would direct operations during communication sessions

with the probe. At 1600 MT (1300 UT) telemetry was received and to everybody's

surprise everything worked well onboard the spacecraft. During this communications

session the probe made its closest approach to the Moon at 1416 UT on 6

October 1959 when Luna 3 passed over the lunar south pole at a distance

7884 km from the moon's centre.

Jodrell Bank observed Luna-3 again (11): "Signals received Oct. 6 183.6 Mc/s only. 1342-1405.40 UT:15 sec on 15 sec off (probably the off period represents a frequency shift). 1405.40-1409.30 UT: No signals in band. 1409.30-1510 UT: usual bleeps. 1510-1538 UT: Modulation as in first period." There were two signals in the band with about 5 kHz separation (11). Was the silence at 1405.40-1409.30 UT caused by the probe's passing behind the edge of the moon?

Chertok (1) recalls that after the communications session all went out with Boguslavskiy to smoke. An ice-cold wind was blowing while the men watched the coastal resort area in the light of the setting sun. Boguslavskiy pointed out a naval vessel at sea that was there to check for radio interference. Korolev demanded that a plan was drawn up for operations the following morning when the pictures of the Moon were to be taken. At that point the designer of the Yenisey imaging system, Brazlawez, worried that the available film in the image recording system was not sufficient and pointed out that the idea was that Korolev's flight from Moscow should have brought extra film. Korolev was furious, but arranged via Rudnev that another Tu-104 would take the film from Moscow to Simferopol where it would be fetched by helicopter.

Korolev finally left Koshka

mountain for a hotel in Nishnaja Orenada near Yalta but left Ostashev at

Kochka overnight. A sumptuous dinner was ready even thorough Korolev and

his party arrived near midnight. Korolev ordered that nobody should drink

alcohol because they needed to leave at 6 a.m. They got only four hours

of sleep.

Korolev finally left Koshka

mountain for a hotel in Nishnaja Orenada near Yalta but left Ostashev at

Kochka overnight. A sumptuous dinner was ready even thorough Korolev and

his party arrived near midnight. Korolev ordered that nobody should drink

alcohol because they needed to leave at 6 a.m. They got only four hours

of sleep.

The 29 exposures of the moon's far side were taken at 0330-0410 UT on 7 October 1959 when the probe was 65567-68785 km from the moon's centre (7). Intermittent telemetry was received at the start of the picture-taking session, but to save power telemetry was switched off. Keldysh called NII-4 to check on the trajectory. Ochozimski at the department of applied mathematics at the Steklov institute of the USSR Academy of Sciences was responsible for trajectory calculations together with Elyasberg at OKB-1 and the NII-4 institute. The computations were made on a computer at the Steklov institute. The reply from NII-4 was that "to be on the safe side we have re-calculated the trajectory data three times and the probe has not approached closer to the Moon than 7000 km". (The actual closest approach was 7884 km from the moon's centre).

What Severny did not know, but probably Chertok, was revealed 45 years later in Novosti Kosmonavtiki (13) of August 2000: radiation-tolerant film from U.S. high-altitude "Genetrix" spy balloons was used in the "Yenisey" imaging system!: (rough translation by Babelfish edited by S.G.)"....The history of that used in the camera the "Yenisey" of the film of the type AB with a width of 35 mm is sufficiently amusing. According to the evidence of the deputy chief designer of the "Yenisey" Bratslavtsa and of leading engineer of the onboard camera Yu.P.Lagutina, our industry by that time yet did not master the production of the film, which satisfied all requirements for "Yenisey". But the situation was rescued by the fact that in the second half of the 50's the USA used balloons for reconnaissance purposes. The possibility of their application for the reconnaissance was based on the special features of the airstreams above our country - constant displacements of air masses from the West to the east. The balloons, supplied with special photographic equipment, were started from the military bases of the USA in the countries of West Europe and, carried by air streams, appeared above the USSR, photographing the territory of our country along the path of motion. .... Certain quantity of film from these balloon spies proved to be in the academy of the name of A.F.Mozhayskogo, with which collaborated with VNII television. After a study of the mentioned film it turned out that it from its parameters was suitable for the use in onboard equipment "Yenisey". Then was accepted, secretly from the high authorities, the solution to cut it into the required dimension, to perforate and to use for photographing of the hidden side of the moon. Hence becomes clear a somewhat mischievous designation of the type of film AB - "American ball(oon)s"."

Here is Bratslavets own story about it.

|

|

Chertok's

book indicates that the images were received on 7 October and that Korolev

was present while the images appeared on the thermo-paper. Chertok

sat next to Boguslavskiy as the first pictures appeared but they were disappointing

- only showed that the

Chertok's

book indicates that the images were received on 7 October and that Korolev

was present while the images appeared on the thermo-paper. Chertok

sat next to Boguslavskiy as the first pictures appeared but they were disappointing

- only showed that the  Moon

was round! Later during the transmission the image quality improved. Whether

or not a later transmission of images was made is not clear from Chertok's

book. Very late that evening (7 October) Korolev and his party returned

to the hotel in Nishnaja Orenada and this time Ostashev came with them

and the government wine and vodka cellar was utilized.

Moon

was round! Later during the transmission the image quality improved. Whether

or not a later transmission of images was made is not clear from Chertok's

book. Very late that evening (7 October) Korolev and his party returned

to the hotel in Nishnaja Orenada and this time Ostashev came with them

and the government wine and vodka cellar was utilized.

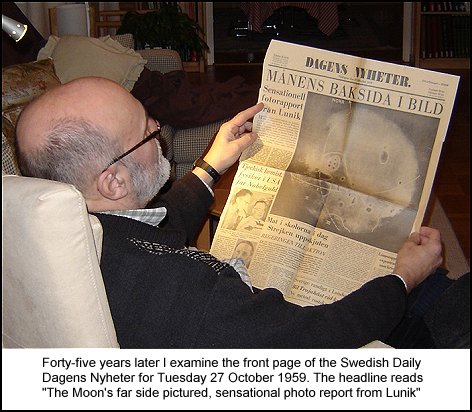

On Monday 19 October 1959 newspapers (9) reported that Moscow media circles had started to talk about the fact that pictures had been taken of the moon. These reports appeared after the probe had come close enough to the Earth to provide sufficient picture quality. Had the transmission of pictures failed the rumors would never had started, it was speculated (9). The pictures of the moon's far side were distributed by tele-photo from Moscow late on Monday (UT) 26 October 1959 and created another space age media frenzy. According to newspaper reports at the time the picture transmission to Earth took place on 18 October 1959 (10).

Jodrell Bank kept up contacts with the Russians even after their publication of the far side pictures. On 1 November 1959 a telegram was sent to AN USSR asking for "co-ordinates for the next transmission from Luna 3", and the first batch of tapes of signals from Luna 2 and 3 were sent to Prof. Nesmeyanov of AN USSR on 9 December 1959. In the accompanying letter Prof. Lovell thanked the Academy for the data with pointing information for the Jodrell Bank telescope. The final batch of Luna 3 tapes were sent to Akademi Nauk on 14 January 1960. The story about Jodrell Bank's reception of Luna 3 signals could have ended here, but there is an interesting epilogue: On 17 January 1961 the director of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, William Pickering, wrote to find out if Jodrell Bank had recorded pictures from Luna 3 and if JPL could have copies of the tapes. Prof. Lovell replied on 20 January 1961 by saying that "Yes, we have a considerable number of tape recordings", and that he had asked Dr. J.H. Thomson to find the tapes, copy them and send them to JPL. Probably the CIA analyzed the tapes sent to Dr Pickering, because in 1994, three decades later, a secret American assessment (6) of Jodrell Bank's Luna 3 recordings was declassified:

"The

very weak signals returning to Earth from Lunik III could not be picked

up by standard Elint collection facilities and equipment. Through the co-operation

of the University of Manchester in England, therefore, use of the 250-foot

radiotelescope at Jodrell Bank was obtained. The Soviets announced that

pictures of the far side of the moon were taken between 0330 and

0410 UT on 7 October 1959. Jodrell Bank succeeded in getting a signal on

the announced frequency of 183.6 megacycles between 1410 and 1445 UT that

date. A ten -hour lag behind the actual picture-taking is not excessive:

the film had to be developed, and then the electronic scanning and transmission

had to wait until rotation of the Earth brought the Soviet deep-space station

in the Crimea into position to pick up the signal. The graduate students

working for Sir Bernard Lovell at Jodrell Bank, however, in recording their

intercept, narrowed the receiver bandwidth so far, in order to increase

signal-to-noise ratio, that they "clipped off" much of the video information.

Confirmation that the Lunik III pictures released by the Soviets were valid

thus rested on a single poorly recorded intercept from which it could be

judged only that the picture was more likely of a test pattern than of

the moon. The signal bandwidth, however, was compatible with the parameters

announced by the Soviets, and on the basis of technical extrapolation it

could be concluded that the Soviet lunar pictures were authentic."

"The

very weak signals returning to Earth from Lunik III could not be picked

up by standard Elint collection facilities and equipment. Through the co-operation

of the University of Manchester in England, therefore, use of the 250-foot

radiotelescope at Jodrell Bank was obtained. The Soviets announced that

pictures of the far side of the moon were taken between 0330 and

0410 UT on 7 October 1959. Jodrell Bank succeeded in getting a signal on

the announced frequency of 183.6 megacycles between 1410 and 1445 UT that

date. A ten -hour lag behind the actual picture-taking is not excessive:

the film had to be developed, and then the electronic scanning and transmission

had to wait until rotation of the Earth brought the Soviet deep-space station

in the Crimea into position to pick up the signal. The graduate students

working for Sir Bernard Lovell at Jodrell Bank, however, in recording their

intercept, narrowed the receiver bandwidth so far, in order to increase

signal-to-noise ratio, that they "clipped off" much of the video information.

Confirmation that the Lunik III pictures released by the Soviets were valid

thus rested on a single poorly recorded intercept from which it could be

judged only that the picture was more likely of a test pattern than of

the moon. The signal bandwidth, however, was compatible with the parameters

announced by the Soviets, and on the basis of technical extrapolation it

could be concluded that the Soviet lunar pictures were authentic."

This

assessment is interesting. In my opinion the picture transmission took

place on 7 October, but also perhaps some 10 days later after which date

the rumors in Moscow about the reception became rampant (9).

In (7) it is mentioned that two transmission

rates were available: "a slower transmission at great distances, and

a faster transmission on approaching the Earth" and that image transmissions

were made from distance of 467000 km (near apogee of the post-flyby trajectory).

Perhaps the pictures sent at apogee were not good enough for publication

but those received later were. We know that the pictures were transmitted

in some kind of facsimile format, frequency-modulated on the carrier. So

it seems that there were pictures sent on 7 October, but exactly when did

the second transmission - if any - take place?

This

assessment is interesting. In my opinion the picture transmission took

place on 7 October, but also perhaps some 10 days later after which date

the rumors in Moscow about the reception became rampant (9).

In (7) it is mentioned that two transmission

rates were available: "a slower transmission at great distances, and

a faster transmission on approaching the Earth" and that image transmissions

were made from distance of 467000 km (near apogee of the post-flyby trajectory).

Perhaps the pictures sent at apogee were not good enough for publication

but those received later were. We know that the pictures were transmitted

in some kind of facsimile format, frequency-modulated on the carrier. So

it seems that there were pictures sent on 7 October, but exactly when did

the second transmission - if any - take place?

In (17) there are graphs showing the signal strength on 183.6 MHz during the flight of Luna-3. Clearly, signal levels on 5 October were very low (see figure below). However, the interesting thing about this reference is that transmission times after the images were taken near the Moon can be deduced (see table above left). The signal strength on the 16 and 17 October was very much better than nearer the Moon. Probably, this is when the good pictures were received.

The camera held 40 frames of film, and 12 images were received via frequency-modulated analog video (some reports claim 17 images were received). The full moon appears to have very little detailed texture, because the lunar mountains and terrain casts no shadows when lit from overhead. The fine stiple seen in some images may be the video subcarrier. .."

Six of the Luna-3 frames have been published and can be found at Don P. Mitchell's excellent site.